Police Violence

Widespread protests in response to the murder of George Floyd in summer 2020 brought the issue of American police violence and acts of police brutality into worldwide public attention. Police violence, however, is not new, and it exists in a long historical continuum of inequities within law enforcement and the criminal legal system. Biased policing practices, militarization of law enforcement, and mass incarceration have been long standing issues that disproportionately impact Black and Hispanic/Latino communities. Over half a century ago, then-President Lyndon Johnson created a federal commission, referred to as the Kerner Commission, to investigate causes for civil unrest in American cities. The commission found that the primary drivers of violence and unrest were police brutality and systemic racial inequities. Despite these findings, the federal government has taken a law and order approach to address violence and social unrest, increasingly relying on police and the criminal legal system rather than addressing the root causes of violence. As a result, many of the same issues cited in the 1968 Kerner commission report—issues of police violence and deep distrust of law enforcement—persist today.1

Addressing police violence is essential to addressing our nation’s persistently high gun homicide rate.

When police violence involves the unjustified threat and use of a firearm, it is a form of gun violence. Each year in the United States, more than a thousand people are shot and killed by police, and tens of thousands more suffer from gunshot injuries and the psychological harm from being threatened by an armed officer. Other forms of police violence, like discriminatory policing practices and misconduct, don’t always involve the use or threat of a firearm, but they are closely linked to the issues of gun violence.

The role of the police is to uphold the law and prevent acts of violence, sometimes through the use of justified armed force. Yet, when armed officers perpetrate violence, they are inflicting the very harm they are sworn to protect against, and this undermines law enforcement’s ability to reduce violence. As a result, communities impacted by police violence lose trust in the criminal legal system, are hesitant to report criminal activity or act as witnesses in criminal investigations and more likely to turn to informal forms of justice through retaliatory gun violence. In short, police violence harms the physical and psychological health of entire communities, and it fuels cycles of distrust in the criminal legal system that contributes to increased community gun violence.

The physical and psychological forms of police violence can inflict a lasting toll on entire communities, including those who have been victimized as well as their family members, friends, and neighbors. These physical and psychological effects often put further stress on already strained, disinvested neighborhoods.

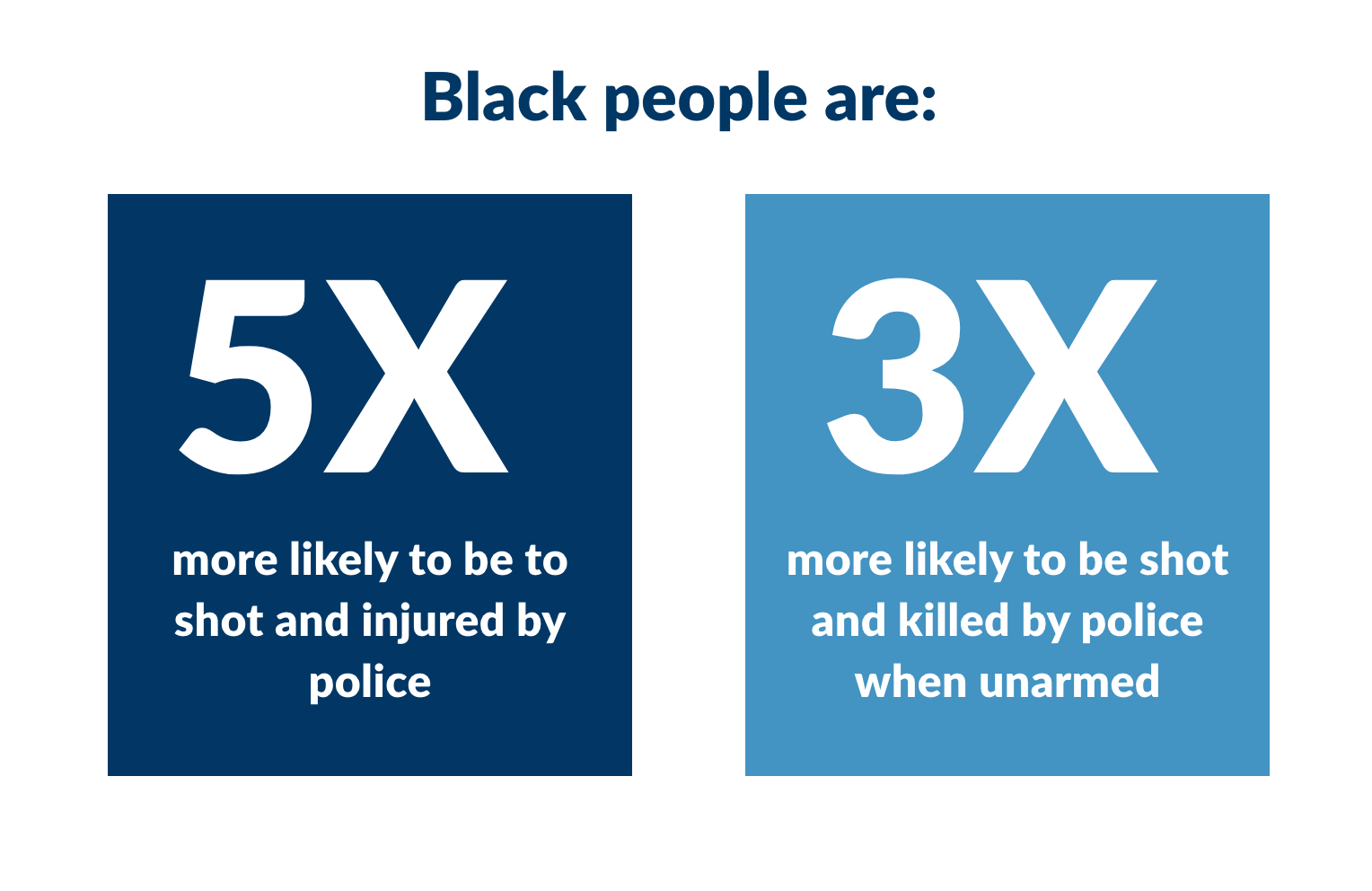

Physical police violence, such as baton beatings, chokeholds, tasers, or shootings, can leave lasting physical harm to its countless victims including physical disability, emotional trauma, and death. Each year an estimated 51,000 Americans are admitted into emergency departments for injuries inflicted by law enforcement and more than 1,000 are killed.2 Black people are disproportionately impacted by this physical violence; Black people age 15-34 are nearly five times more likely than white people of the same age range to be admitted into the emergency department for a police-inflicted injury.3 Unarmed black people are over three times more likely to be shot and killed by police compared to white people.4

Psychological police violence such as threats, intimidation, sexual harassment, humiliating and degrading treatment, or verbal abuse often occurs in conjunction with unconstitutional and discriminatory policing practices like stops and searches without probable cause. Like other types of police violence, these practices are disproportionately used on Black and Hispanic/Latino men, who are routinely stopped, suspected of a crime, intimidated, and patted down, often aggressively, by police officers. Compared to their peers of races and ethnicities, multiracial or Black youth were more likely to have witnessed threats and experienced use of force, racial slurs by officers. As a result, they were more likely to report feeling scared, unsafe, and/or angry when witnessing police stops.5

A Department of Justice investigation into the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) highlights the reality of discriminatory policing many Black people experience The investigation found that the BPD conducted hundreds of thousands of stops each year, routinely stopping and searching Black people without any reasonable suspicion with only 3.7% of stops resulting in a citation or arrest. The report found that over four years, 410 individuals were stopped on at least 10 separate occasions, and countless individuals were stopped multiple times within the same week without facing any charges.6

Individuals exposed to stop-and-frisk practices like these routinely report long-term psychological trauma, humiliation, and fear.7,8,9 Individuals who have been victimized by police violence are at an increased risk for post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, and suicide. Exposure to trauma can trigger hypervigilance, a state of increased alertness that is meant to help detect and respond to threats. Intended to be a finite state that ends after the threat is no longer present, chronic hypervigilance can lead to poor physical health, antisocial behavior, and an increased likelihood of aggression.9,10,11 Family members of the person who was victimized by police also experience challenges with mental health. Mothers regularly bear the brunt of such mental health impacts, often experiencing self-blame, flashbacks, deep sadness, anger, and isolation from friends and family.12

The psychological impacts of police violence have a ripple effect on the larger community. One study examined the mental health outcomes of Black people following the killing of unarmed Black individuals by police. It found that each additional police killing of an unarmed Black person was associated with a marked deterioration in mental health for three months following the killing among Black respondents.13 Another study interviewed Black people about their emotional experiences following highly publicized news of Black people being killed by police. Interviewees expressed profound, debilitating sadness that interfered with their ability to complete daily tasks or engage in their work, and for some, was associated with suicidal ideation or substance abuse.14 The interviewees also discussed their chronic fear of dying at the hands of police, creating an intense and persistent state of hyperarousal that resulted in visceral, emotional responses when interacting with law enforcement or hearing the sound of sirens.

The killing of unarmed, law-abiding Black people is a painful reminder of the expendability of Black lives that creates a profound sense of powerlessness and helplessness in many Black people. The traumatic nature of police violence, the tendency for the murder to be ruled as justified, or for law enforcement to be acquitted at trial also contribute to the sense of helplessness and powerlessness.16

Police violence and widespread misconduct can also impact how entire communities interact with public institutions, fuelling a general distrust in schools, hospitals and city services and often a withdrawal from civic life.17,18 For example, one study found that police violence within a given neighborhood had a chilling effect on that neighborhood’s willingness to request city services, as documented by a decrease in 311 calls for service.19 Other studies have found that police violence exposure within a community is associated with poor school performance and lower rates of high school completion. Researchers found that on average each additional fatal police shooting within a given county caused three additional high school students to drop out.20

Mass incarceration and Violence

“Tough-on-crime” policing practices that proliferated over the past 40 years have led to the current era of mass incarceration, disproportionately impacting Black communities. Research consistently highlights racial disparities at virtually every step within the criminal justice system. Black males are stopped by police, arrested, denied bail, wrongfully convicted, issued longer sentences, and shot by police at much higher rates than white people.21 While Black people make up 13% of the U.S. population, they account for 40% of the country’s total incarcerated population and a third of state and federal prisoners.22,23 Mass incarceration has a devastating effect on communities by separating families and limiting the ability of both the formerly incarcerated and their social networks to build social and economic capital. While mass incarceration isn’t directly a form of police gun violence, it is a form of violence inflicted by the state, often through the use of discriminatory policing practices.

Police violence can contribute to the cycles of community gun violence by eroding police legitimacy, a vital component in reducing community gun violence. When communities view the police force as legitimate they are more willing to participate in efforts to identify and detain those responsible for committing acts of gun violence, and to intervene before conflicts develop into shootings. Likewise, when police legitimacy is strong, victims of violence feel safe and can rely on formal channels of justice to bring about closure, instead of resorting to retaliation.24

Police brutality and widespread discrimination undermine police legitimacy, and contribute to community gun violence. In many Black and Brown communities distrust in law enforcement stems from a legacy of racist policies, practices, and abuses, often carried out by police. The ongoing crisis of mass incarceration and police brutality compounds this history.25 Unsurprisingly, when individuals experience police discrimination or brutality they are less likely to trust or rely on law enforcement, and reluctant to report criminal activity or act as witnesses in criminal investigations. Instead, some rely on informal channels of justice—like retaliatory violence—to resolve conflict.26

A 2016 study examined the relationships between police brutality, police legitimacy, and homicide rates in Milwaukee, Wisconsin through the highly publicized, brutal beating of an unarmed Black man, Frank Jude, by Milwaukee police officers in 2004. The authors found that in the year after the beating, calls for police services dropped dramatically in the city, particularly in underserved Black and Brown neighborhoods. In the year following the beating, there were 22,200 fewer 911 calls, coinciding with a spike in homicides. In the six months following this beating, homicides in Milwaukee increased by 32%.27 The authors conclude that this one act of police brutality eroded trust in law enforcement and likely contributed to increases in gun violence, underscoring how police brutality is both unconscionable in its own right and may fuel community gun violence.

Strong gun violence prevention laws must be paired with measures to ensure police accountability in order for police officers to enforce gun laws in an effective and equitable manner. Many Black and Brown communities across America are apprehensive to trust law enforcement and often are reluctant to partner with police to act as witnesses and prevent violence. Given the long history of police violence, often reinforced by the criminal legal system, this reticence is understandable. Policymakers and police departments must work to mend these relationships by building authentic relationships with communities, improving mechanisms of transparency and accountability, and enacting police reform.

Challenges faced by law enforcement

Police officers, as first responders, are often forced to assess difficult situations and make quick decisions when responding to crises. While it is imperative to implement policing reforms to address law enforcement misconduct and abuses, it is also important to acknowledge the challenges officers are confronted with armed civilians. In the vast majority of police shootings, the civilian is armed with a firearm.28 When law enforcement is dispatched to a household or a situation in which a firearm is present, it increases the lethality for both the civilian and the police officer.29,30

Officers shot in the line of duty

According to the Gun Violence Archive, from 2014-2019, 1,467 local and state law enforcement officers were shot in 1,185 incidents, 249 of which were fatal. On average, 245 officers were shot per year, 42 of them fatally.31 Many officers who are shot and killed in the line of duty are responding to domestic violence situations. From 2015-2016, domestic disturbance calls accounted for 41% of all line-of-duty police deaths and all but one involved a firearm.32

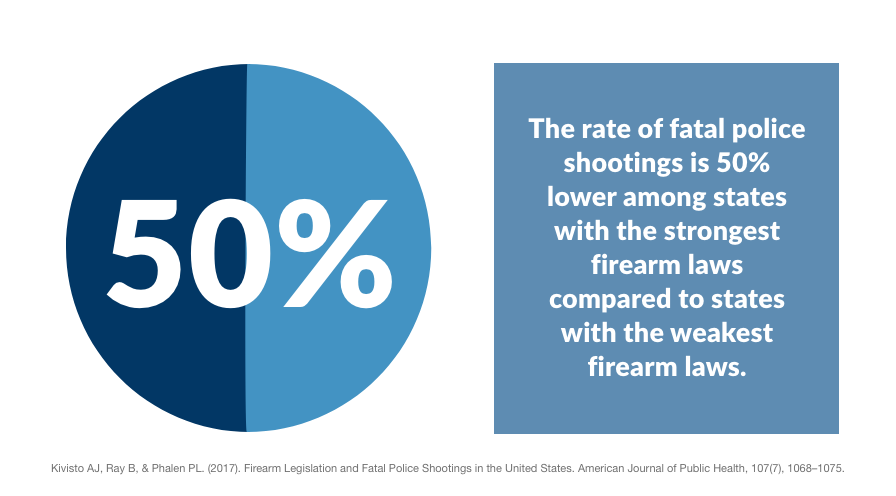

The high rate of civilian firearm ownership in the United States increases the likelihood that police officers will interact with armed civilians, threatening the lives of everyone at the scene. In addition, law enforcement officers are often likely to assume all individuals are armed and are more likely to use lethal force on unarmed individuals. Studies show there is a strong association between the statewide rate of fatal police shootings and the statewide prevalence of firearms.33 Another study examined how state-level firearm legislation, such as background checks, safe storage, and gun trafficking prevention laws, are linked to a decrease in fatal police shootings. States with the strongest firearm laws were associated with a rate of fatal police shootings more than 50% lower than states with the weakest firearm laws.34 In practice, however, many U.S. states continue to have lax firearm laws that leave both police officers and armed civilians unprotected and at high risk of violent escalation. Government leaders need to introduce and enforce stronger gun laws to protect officers in the line of duty and address the challenges officers often encounter.

Incomplete federal data on fatal police shootings

The federal government does not provide a complete count of fatal police shootings that occur in the United States each year.36 The tallies reported by both the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) account for only a fraction of the true number of fatal police shootings. The FBI data is voluntarily reported by local police departments and is thus not comprehensive. Likewise, the CDC data on fatal police shootings undercounts the true total because medical examiners or coroners often list the cause of death as something other than a police shooting.37 To address this gap, several media sources have tracked police-involved shootings in recent years, most notably the Washington Post’s Fatal Force database, finding more than double the number of fatal shootings than are reported in FBI and CDC databases.

Databases like the Fatal Force database have informed citizens and researchers alike around the burden of police violence in America but do not replace the need for a comprehensive government-sponsored database that collects data on each police-involved injury. Compulsory and comprehensive data collection at the local level, reporting to the federal government, and transparency in the public dissemination of data will be critical for understanding police violence and developing evidence-based solutions to minimize police-involved shootings.

Fatal police shootings: What does the data show?

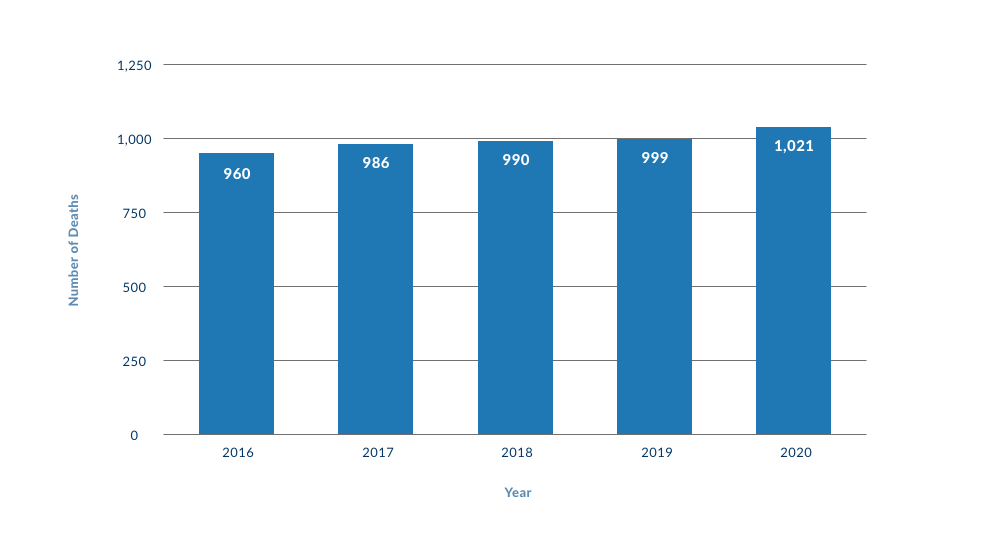

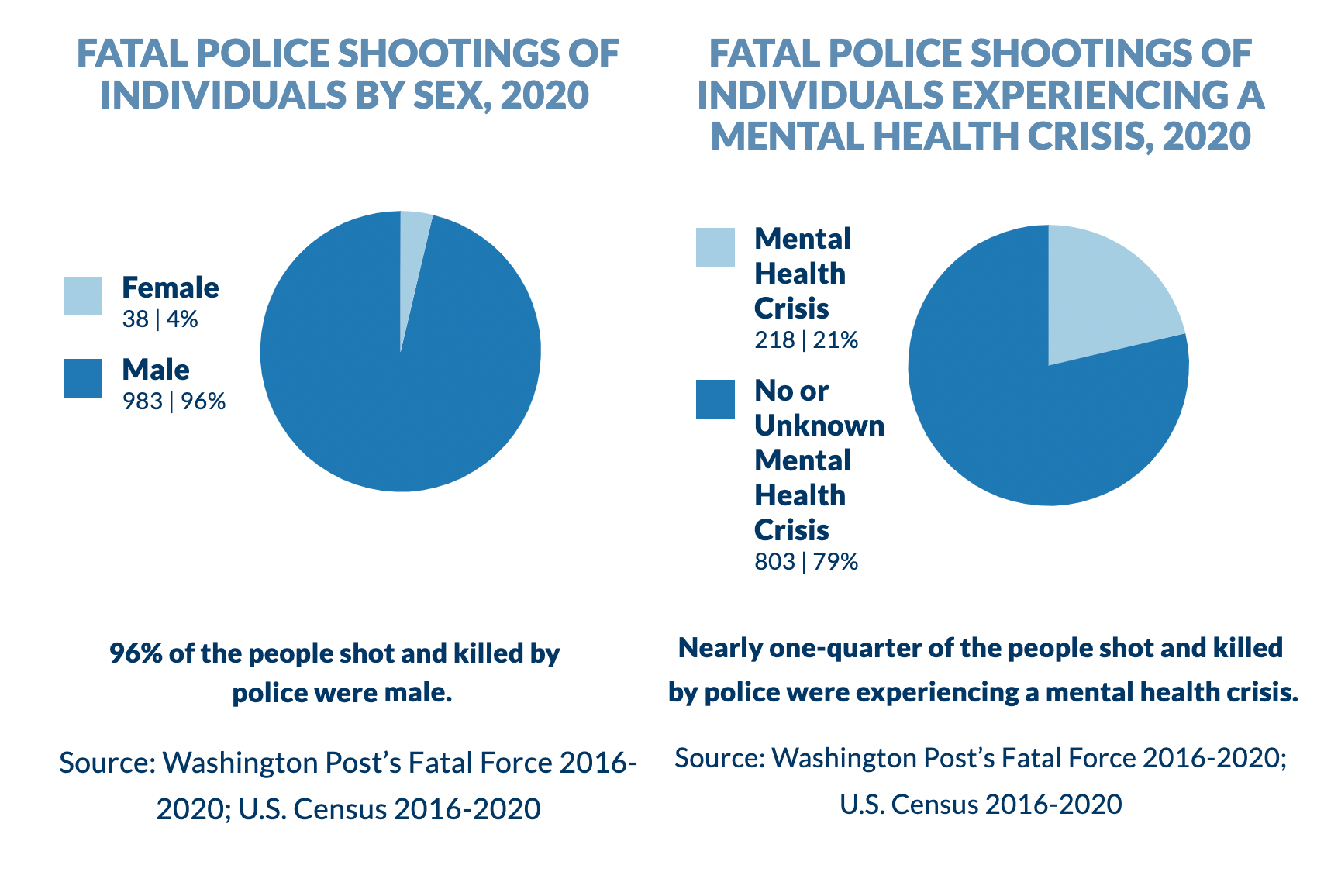

Washington Post’s Fatal Force has collected data on fatal police shootings in the United States from 2015-2021, showing that the number of fatal police shootings have increased gradually every year since 2016, and surpassed 1,000 for the first time in 2020.38 Data results reveal the disproportionate impacts of police shootings on specific demographic groups and geographic areas:

- In 2020, 96% of the people shot and killed by police were male.

- People between 18-44 years old were more at risk of being shot and killed by police in 2020 than other age groups.

- From 2016-2020, nearly one-quarter (23%) of the people shot and killed by police were experiencing a mental health crisis. Individuals living with a severe mental illness are 16 times more likely to be fatally shot by police.39

- Racial minorities were more likely to be shot by police despite being unarmed. From 2016-2020, Black people and Hispanic/Latino people were respectively 3.3 and 1.4 times more likely to be shot by police when they were completely unarmed compared to white people.

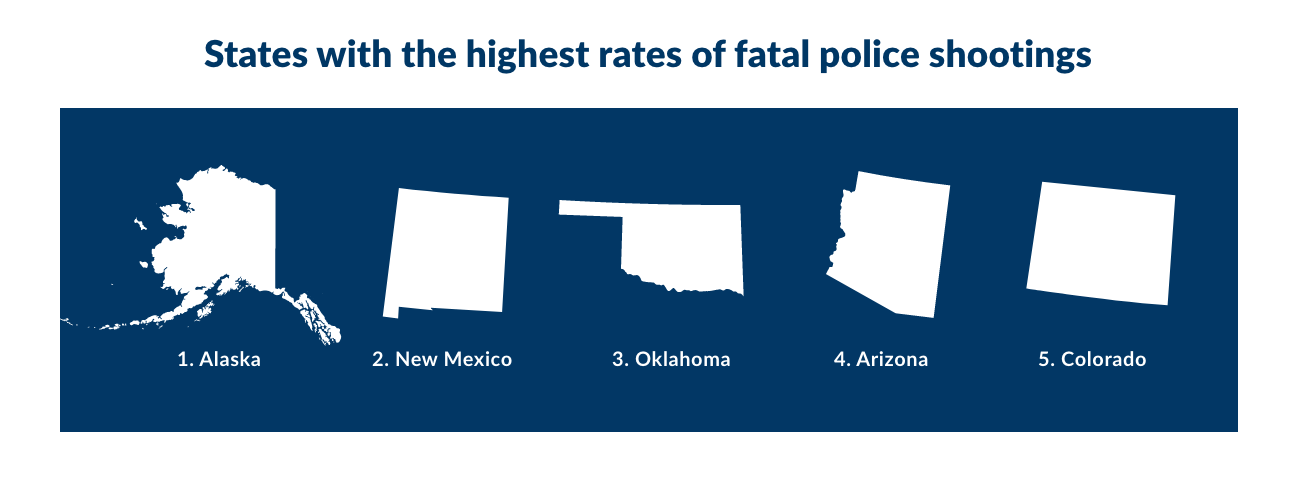

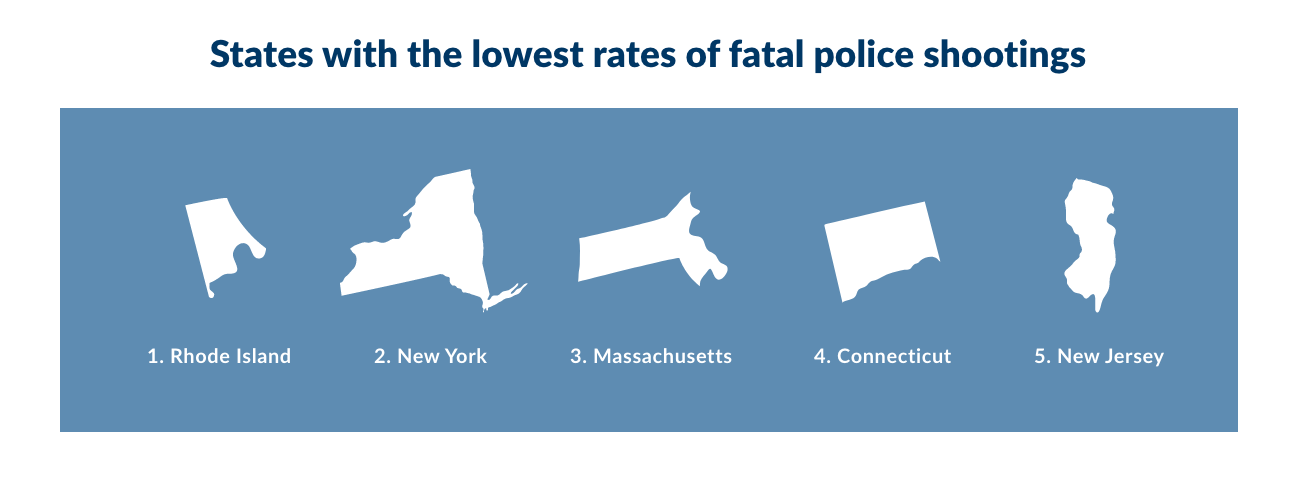

- There is wide variation in the rates of fatal police shootings by state. From 2015-2019, someone living in Alaska, the state with the highest rates of fatal police shootings, was 14 times more likely to be shot and killed by police compared to someone living in Rhode Island, the state with the lowest rate. The state variation is likely driven by a number of demographic, social and political factors including the prevalence of gun ownership and state gun laws.

Police Shooting Fatalities, 2016-2020

Despite the growing awareness of police violence, the number of fatal police shootings has increased slightly from 2016-2020.Source: Washington Post’s Fatal Force 2016-2020; U.S. Census 2016-2020

Police Shooting Fatalities, 2016-2020

Number of Deaths

Year

Despite the growing awareness of police violence, the number of fatal police shootings has increased slightly from 2016-2020.

Source: Washington Post’s Fatal Force 2016-2020; U.S. Census 2016-2020

Fatal Police Shootings of Unarmed Americans by Race/Ethnicity, 2016-2020

Race/Ethnicity

Rate (Per 100,000)

Black people and Hispanic/Latino people were respectively 3.3 and 1.4 times more likely to be shot by police when they were completely unarmed compared to white people.

* There were 14 fatal police shootings of unarmed individuals in which the race/ethnicity of the decedent was unknown, and 6 fatal police shootings where the decedent was either Native American, Asian, or Other.

Source: Washington Post’s Fatal Force 2016-2020; U.S. Census 2016-2020

Fatal Police Shootings by Age Group, 2020

Age Group

Rate (per 100,000)

People between the ages of 18-44 years old were most likely to be shot and killed by police.

Source: Washington Post’s Fatal Force 2016-2020; U.S. Census 2016-2020

Fatal Police Shootings by State, 2016-2020

Rate (Per 100,000)

- 0.08 to 0.28

- 0.29 to 0.49

- 0.50 to 0.70

- 0.71 to 1.03

Source: Washington Post’s Fatal Force 2016-2020; U.S. Census 2016-2020

Source: Washington Post’s Fatal Force 2016-2020; U.S. Census 2016-2020

Source: Washington Post’s Fatal Force 2016-2020; U.S. Census 2016-2020

Police violence is a complex issue that will require a multifaceted public health approach from local, state, and federal policymakers. Policymakers should take the following steps to reduce police violence and begin to rebuild trust between law enforcement and the communities impacted by daily gun violence. While these recommendations are by no means comprehensive, they would help begin to increase police accountability and reduce misconduct.

We recommend reforms that focus on:

- Data tracking and reporting: Police departments should be required to collect and publicly report all instances of police gun violence in a timely manner. Congress should condition federal funding to state and local law enforcement on data reporting compliance. Police departments should be required to report hospitalizations and fatalities caused by police violence to the FBI. The Department of Justice (DOJ) should issue annual reports documenting police killings and hospitalizations in America. The CDC should classify law enforcement related deaths as a notifiable condition allowing public health departments to report data around police killings in real-time. The CDC and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) should conduct an investigation into the causes of misclassification and underreporting of police killings, and they should provide technical assistance to coroners and medical examiners to improve proper classification on death certificates. Comprehensive data collection at the local level, reporting to the federal government, and transparency in the public dissemination of data will be critical for understanding police violence and developing evidence-based solutions to minimize police-involved shootings.

- Strong framework of laws that create mechanisms of accountability and oversight: Federal and state governments should leverage already existing policies that promote police accountability and oversight. For instance, the DOJ can open a formal investigation or a “pattern or practice” into local police departments suspected of unconstitutional policing practices. If the DOJ finds sufficient evidence of misconduct, local police departments are legally required to undergo structural reforms. In addition, federal, state, and local policymakers should pass legislation to ensure that police departments institute widespread reforms. Reports authored by organizations like The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights offer in-depth recommendations to address police violence from leading experts in the field. Policymakers should consider instituting the police reforms recommended by these organizations including the following:

- Require that officers use de-escalation tactics and exhaust all reasonable alternatives before using physical force; provide routine de-escalation training for officers.

- Mandate that police officers use deadly force as a last resort only after they have exhausted all other measures.

- Require officers to intervene when excessive force is used by another officer and immediately report these incidents to superiors.

- Create independent processes to investigate misconduct or excessive use of force.

- Restrict the transfer of military equipment to police and the use of such equipment by police departments.

- Limit the use of SWAT teams and no-knock warrants to only to the most dangerous situations where officers can demonstrate imminent threat of serious bodily harm.

- Ban the use of dangerous neck restraints and other maneuvers that restrict blood or oxygen flow to the brain.

- Require police departments to comprehensively report all use of force instances and create transparent processes to receive and respond to misconduct complaints.

- Prohibit profiling by law enforcement based on race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, disability, proficiency with the English language, immigration status, and housing status.

- Pass strong gun violence prevention laws: Strong gun violence prevention laws can minimize police interactions with individuals who are carrying guns and can reduce the likelihood of a fatal encounter. To help reduce police killings federal, state, and local lawmakers should enact gun violence prevention laws that: 1) prevent the diversion of illegal guns into criminal networks 2) ensure those at high risk for violence cannot gain access to a gun, and 3) limit gun carrying in public places.

- Community engagement and partnerships: Police departments must work towards adopting procedurally just practices outlined in President Barack Obama’s 21st Century Policing Report. Procedural justice requires a long-term commitment from law enforcement leaders to institute a culture in which police see the community as authentic partners and respond to the expressed needs of the community. In order for these partnerships to take root there must be a law enforcement culture of transparency and citizen oversight. Community members should have a voice in the decision-making process and decisions should be made in a fair and neutral way.40,41 When police adopt procedurally just policing techniques to build trust they can more effectively work with community members to solve gun crimes, prevent future violence, and co-produce public safety.

- Partnerships with mental health providers: Law enforcement agencies should partner with behavioral health providers by launching co-responder or crisis intervention models. When a 911 call is made in a city with a co-responder model, the dispatcher is trained to identify the non-violent call and deploy mental health professionals to respond to the person experiencing a behavioral health crisis. If the situation has the potential for violence, both mental health professionals and law enforcement are dispatched with the aim of de-escalation. The partnership and deployment of mental health professionals will minimize the potential for police violence by de-escalating tense situations and by ensuring that those experiencing a crisis receive appropriate behavioral health support.

- Invest in violence prevention and intervention infrastructure: Cities should work to build cooperation between social service agencies, public safety agencies, and community service providers to identify and address specific risk factors for violence within the city, and to identify individuals at highest risk for violence. They should do this through the creation of Offices of Violence Prevention and Homicide Review Commissions.42 All levels of government should invest in community violence intervention programs that can help interrupt cycles of violence, improve trust in civic institutions including law enforcement, and change norms around the use of violence.

Educational materials

- EFSGV. (2020). Police Reform, Legitimacy, and Community Gun Violence. The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence.

Research

- Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. (2018). Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. The Lancet.

- Desmond M, Papachristos AV, & Kirk DS. (2016). Police Violence and Citizen Crime Reporting in the Black Community. American Sociological Review, 81(5), 857–876.

- Hemenway D, Azrael D, Conner A. et al. (2019). Variation in Rates of Fatal Police Shootings across US States: the Role of Firearm Availability. J Urban Health.

- Kivisto AJ, Ray B, & Phalen PL. (2017). Firearm Legislation and Fatal Police Shootings in the United States. American Journal of Public Health.

- Nagin DS. (2020). Firearm Availability and Fatal Police Shootings. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

- Simmons, K. C. (2015). Increasing police accountability: restoring trust and legitimacy through the appointment of independent prosecutors. Wash. UJL & Pol'y, 49, 137.

- Simmons, K. C. (2014). The coming crisis in law enforcement and how federal intervention could promote police accountability in a post-Ferguson United States. Wake Forest L.Rev 2, 101.

- Webster D.W., Crifasi C.K., Williams R.G., Doll Booty M., & Buggs S.A.L. (2020). Reducing Violence and Building Trust: Data to Guide Enforcement of Gun Laws in Baltimore. John Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research.

Additional Resources

- APHA. (2018). Addressing law enforcement violence as a public health issue. American Public Health Association.

- Campaign Zero: #8 Can't Wait

- Center for Policing Equity and Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School Re-imagining Public Safety: Prevent Harm and Lead with the Truth

- Mapping Police Violence

- President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. (2015). Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

- Tate J, Jenkins J, & Rich S. (2021). Fatal Force. Washington Post.

- The Leadership Conference Education Fund. (2019). New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

- Urban Institute’s The National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice: Key Process and Outcome Evaluation Findings.

- What Policing Costs. The Vera Institute.

Last updated January 2022