Extreme Risk Laws

BACKGROUND

Family members are often the first to know when loved ones are in a suicidal crisis or threatening interpersonal violence. In many high profile shootings and firearm suicides, family members saw their loved ones engage in risky behaviors and grew concerned about their risk of harming themselves or others—even before any violence occurred. Given the proper tools, family members and law enforcement, as well as others close to the at-risk individual, have the potential to prevent incidents of interpersonal violence and suicide that take place across this country every day. Yet a gap in most states’ laws makes it difficult for them to intervene.

Extreme risk laws empower law enforcement, and, depending on the jurisdiction, family members, health professionals, and school administrators, among others, to prevent gun tragedies by temporarily removing firearms from individuals at an elevated risk of harm to self or others.

How Extreme Risk Laws Were Developed

The role of the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy

Risk warrants: the precursor to modern extreme risk laws

The first extreme risk law was Connecticut’s “risk warrant,” which passed in 1999 following a mass shooting at the state’s lottery headquarters. Six years later, in 2005, Indiana passed another early version of an extreme risk law. Both laws allow only law enforcement to petition for a warrant.

Developing recommendations for the modern extreme risk law

Extreme risk laws were further developed from risk warrants to the protection orders that are common today by the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy in 2013. Following the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut (a case in which a risk warrant was not sought), the national conversation around preventing gun violence focused on mental illness. To examine the potential relationship between mental illness and gun violence, the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence brought together the nation’s leading researchers, practitioners, and advocates in gun violence prevention, public health, law, and mental health to form the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy (Consortium).

The Consortium found that focusing firearm prohibitions based on mental illness alone was misguided, not supported by research evidence, and stigmatizing. Instead, the Consortium zeroed in on risk factors for violence to self and others that are supported by research. They conceptualized a new type of civil order based on the legal framework of existing domestic violence protection orders and focused on the principles of risk as they relate to firearm access. These recommendations became the basis of the modern extreme risk law.

Passing the nation’s first modern extreme risk law

After the May 2014 mass shooting near the University of California, Santa Barbara campus, community members, law enforcement, and policymakers reflected on how this tragedy could have been averted. The shooter had exhibited dangerous behavior prior to the shooting, and his parents shared their concerns with his therapist who contacted law enforcement. The police briefly interviewed him but had no clear legal authority to intervene and were unable to take action before this tragedy occurred.

In the wake of this shooting, California lawmakers recognized that this gap in California law must be closed. On September 30, 2014, four months after the Santa Barbara shooting, the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence assisted California lawmakers in passing the nation’s first Consortium-recommended extreme risk law, known as a Gun Violence Restraining Order (GVRO), that included both law enforcement and family or household members as petitioners.

Extreme risk laws are passed in states across the country

Over the next six years, sixteen states and the District of Columbia passed extreme risk laws. As of June 2021, nearly half of the U.S. population has access to an extreme risk law.

“Before GVROs were made available in California, we were limited in our capacity to help. Now, if we see an escalation of dangerous behaviors, including risk of suicide, we can file for a GVRO. It is one more tool to keep communities safer from needless gun violence.”

- Lieutenant Eddie Hsueh, Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office

WHAT ARE EXTREME RISK LAWS?

Extreme risk laws (sometimes called Extreme Risk Protection Orders or “Red Flag Laws”)7 are state laws that provide law enforcement and, depending on the jurisdiction, family members, health professionals, and school administrators, among others, a formal legal process to temporarily reduce an individual’s access to firearms if they pose a danger to themselves or others. This legal process may look somewhat different across states, but most are based on the long-standing infrastructure and procedures of domestic violence protection orders (in place in all 50 states).8 It is most often a civil court order, prompted by a petition by a family member or law enforcement officer and issued by a judge upon consideration of the evidence. The order temporarily prohibits a person from possessing or purchasing firearms and provides a process for the removal of firearms already in the person’s possession. In some states, extreme risk laws also prohibit possession of ammunition.

IT’S TIME TO RETIRE THE TERM “RED FLAG LAWS”

“As extreme risk laws have become more mainstream, the question of what to call them has become more important — and the term ‘red flag law’ has become more troubling. Over time — especially after many conversations with our allies in the mental health community — it has become clear that the term ‘red flag law’ is not just a memorable, innocuous nickname. It is a term that has the potential to alienate marginalized groups. And by mischaracterizing the way these laws operate, ‘red flag’ is a term that jeopardizes the policy’s impact. These problems stem from the vague nature of the name ‘red flag.’ Because the term is so indefinite in meaning, it is easy to corrupt. It is easy to mischaracterize the policy’s mechanisms and purpose — whether intentionally or unintentionally.”

- March 2019 Medium blog

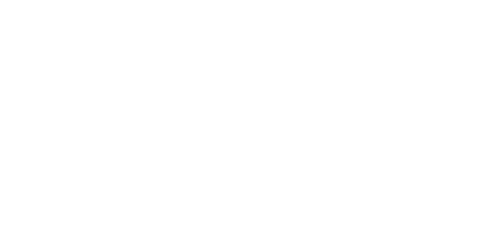

HOW DOES AN EXTREME RISK LAW WORK?

Who May Petition for an Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO)?

Generally, family or household members and law enforcement officers may petition a court for an Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO).9 Some states allow other individuals to petition a court for an ERPO. These individuals include: healthcare professionals,10 employers,11 coworkers,12 and school administrators.13

How Many Types of ERPOs Are There?

There are usually two types of ERPOs: 1) an ex parte ERPO that is available in emergency circumstances. Due to the emergency nature, an ex parte order is issued by a court without notice to the respondent or an opportunity to be heard at the hearing; and 2) a final ERPO. A final ERPO typically lasts up to one year and may only be issued after a noticed hearing at which the respondent has the opportunity to appear and be heard. Both ex parte and final ERPOs are civil, not criminal, orders.

Ex Parte ERPOs

Ex parte ERPOs are typically issued where the petitioner proves that the respondent poses an imminent risk or risk in the near future of harming themselves or someone else by having access to a firearm.14 The duration of an ex parte ERPO and standard of proof that petitioners must meet varies from state to state,15 though generally an ex parte ERPO lasts up to 14 days.16

Final ERPOs

Final ERPOs are typically issued where the petitioner proves by clear and convincing evidence or preponderance of the evidence (depending on the state statute) that the respondent poses a risk of harming themselves or someone else by having access to a firearm.17 In a majority of states, final ERPOs may last up to one year. 18

Termination and Renewal of ERPOs

ERPOs are time limited and may be terminated, renewed, or allowed to expire. Respondents typically have at least one opportunity to request a hearing for termination of an order before it is set to expire.19 At the hearing, the respondent generally has the burden of proving that they no longer pose the risk that justified the initial order. Most ERPO laws also allow a petitioner to request a renewal of an order.20 At a renewal hearing, the petitioner usually bears the same burden of proof as in the original hearing. When the order is terminated or allowed to expire and the respondent is not otherwise prohibited from purchasing or possessing a firearm (as determined through a background check), the party temporarily holding the respondent’s firearms may return them to the respondent.

For a basic overview of how extreme risk laws generally work, see the infographic below.

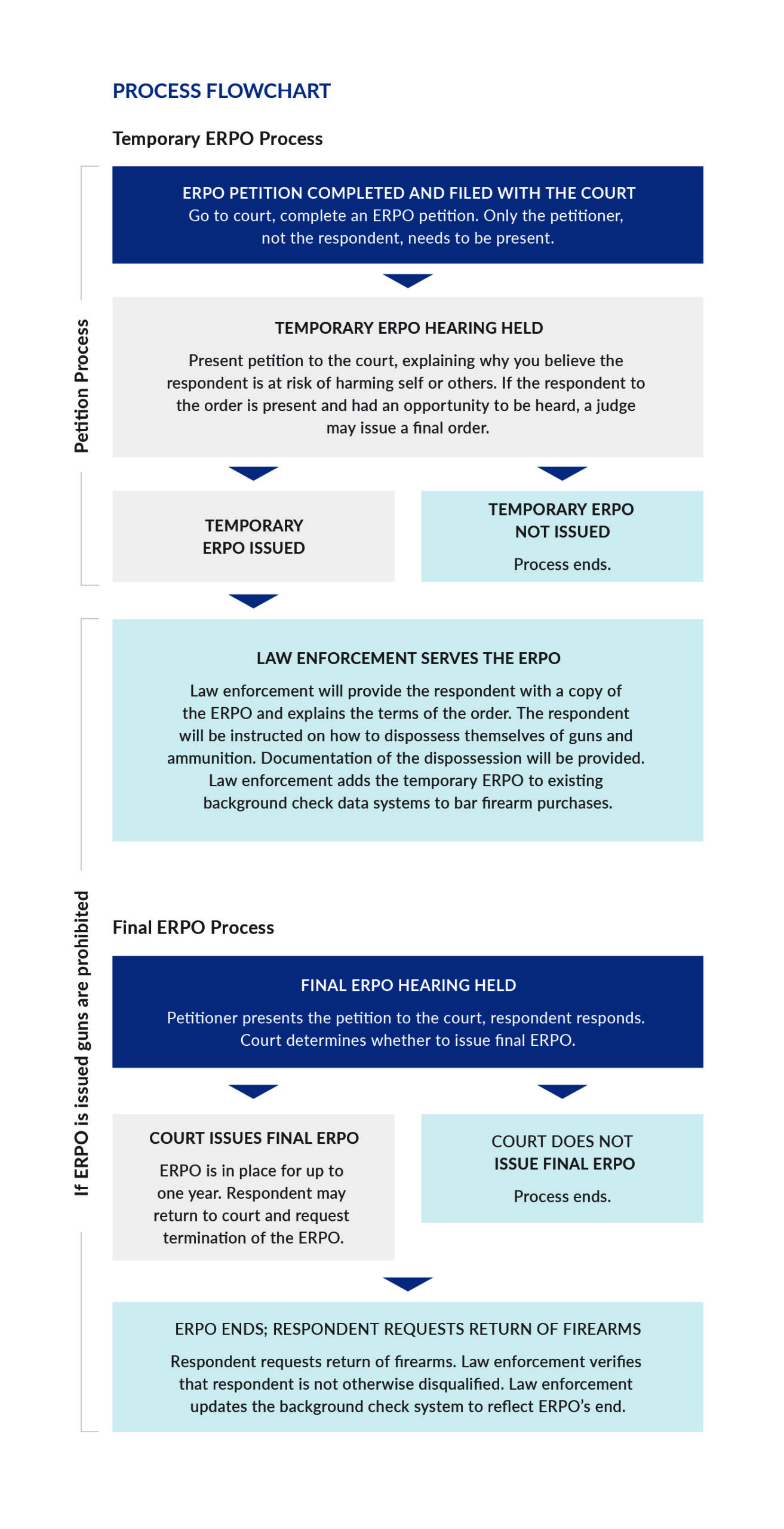

To learn more about the specific process of obtaining an ERPO in each state please visit The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg American Health Initiative – Extreme Risk Protection Order: A Tool to Save Lives. The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence serves as a partner on this innovative project to provide in-depth resources for implementers, advocacy groups, and concerned citizens.

What Evidence Does A Judge Consider Before Issuing An Extreme Risk Order?

The evidence a judge may consider when issuing an order for firearm removal varies among states. It generally includes, but is not limited to:

- Recent acts or threats of violence towards self or others.

- History of threatening or dangerous behavior.

- Convictions of domestic violence misdemeanors and/or other violent misdemeanors.

- History of, or current, risky alcohol or controlled substance use.

- Recent violation of a domestic violence protective order.

- Unlawful or reckless use, display, or brandishing of a firearm.

- Recent acquisition of firearms, ammunition, or other deadly weapons.

- Cruelty to animals.

Mental illness should not be considered by a judge as a risk factor

The factors considered should be based on the evidence of risky behavior, not on a mental illness diagnosis. Mental illness is not a reliable predictor for interpersonal violence. While some mental illnesses, like depression, are associated with suicide and other forms of self-harm, they are not standalone predictors of suicide.

CASE EXAMPLES: HOW EXTREME RISK LAWS CAN PREVENT VIOLENCE

Suicide

After receiving an eviction notice, a 57-year-old man from Washington made suicidal statements involving his firearm. Police used Washington’s extreme risk law to temporarily remove the gun and protect this man during the suicidal crisis.26

In Washington, a woman filed an ERPO against her boyfriend after he had previously attempted suicide and now wanted to purchase a firearm. At the hearing, the couple came to court together, holding hands. The man had no objection to the order and was thankful that someone cared enough to ensure he did not have access to a gun during this suicidal crisis.27

Interpersonal Violence

A man in Oregon planned to shoot his boss who had just fired him. His sister stopped him from returning to his former employer. An ERPO was issued.28

A 27-year-old armed security guard in Florida fired his gun into the air and pulled a knife during two arguments with his neighbors. A judge issued a temporary order.29

School Shootings

Two Vermont middle school students were plotting a school shooting, with one student volunteering to use a relative’s guns. A separate student overheard the plan and alerted authorities. An order was issued to remove the guns from the student’s home.30

A Maryland student posted Snapchats of him holding a rifle and threatening a school shooting. Police issued a temporary order and removed a pair of loaded assault rifles and ammunition.31

Mass shootings

A Washington man posted numerous mass shooting threats on social media including stating that he planned on shooting 30 Jews, along with pictures of Nazi artifacts and of his gun collection. An order was granted and 12 firearms were removed.32

In California, a 24-year-old man threatened to kill his family and employees of the family business. He had a history of threatening employees and was previously convicted for a weapons offense. The man’s mother petitioned for a temporary order and 26 firearms were surrendered. Subsequently, a final order was issued.33

Domestic Violence

In California, a 38-year-old man made threats to kill himself, his wife, and their young child. An order was issued after his wife heard him distraught and crying in the bathroom, cocking his gun. 34

In California, a 40-year-old man sent a text message to his fiancé threatening to shoot her. He then visited his fiancé’s ex-boyfriend and threatened to kill him, while holding a knife behind his back. Police used California’s extreme risk law to temporarily remove a handgun and an AR-15 from the man.35

Dementia

In California, an 81-year-old man, known to be in the early stages of dementia, threatened to shoot his wife and a neighbor. His 75-year-old wife escaped by climbing a fence. An order was issued.36

Harassment

A man in Florida confronted Black construction workers with two large knives and yelled racial slurs before slashing their car. An order was issued and police removed two handguns.37

Alcohol and Guns

An intoxicated California man thought he was shooting at raccoons and rats but was shooting into his neighbors’ yards. Terrified neighbors called the police and an order was filed.38

RESEARCH FINDS THAT EXTREME RISK LAWS SAVE LIVES

Peer-reviewed studies have examined the impact of extreme risk laws in Connecticut, Indiana, and California and found evidence that these laws have helped prevent firearm deaths.

An analysis of Connecticut’s extreme risk law found that from the passage of the law in 1999 to 2013:39

- 762 firearm removal cases were issued and police found firearms in 99% of cases, removing an average of seven guns per subject.

- Suicidality or self-injury was a listed concern in ≥61% of cases where such material was available.

- The majority of cases involved middle-aged or older men.

- For every 10-20 firearm removals issued, one life was saved.

Source: Swanson JW, et al. (2017).

A 2019 study of Indiana’s extreme risk law found that Indiana’s extreme risk law (2006-2013) was similarly effective as Connecticut’s law in preventing suicide.40

- 395 firearm removal cases were issued and 1,079 firearms were temporarily removed.

- In nearly 70% of these cases, suicidal ideation was cited as the reason the order was issued.

- The majority of cases involved White men.

- One suicide was prevented for every 10 firearm removals issued.

A 2018 study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Services estimated the impact of extreme risk laws. This study found:41

- Indiana’s extreme risk law led to a 7.5% reduction in firearm suicides.

- Connecticut’s extreme risk law led to a 13.7% reduction in firearm suicides.

A 2019 study examined how extreme risk laws may prevent mass shootings.42

- Researchers analyzed 159 extreme risk orders issued in California from 2016 to 2018.

- In 21 orders, the subject showed clear signs that they intended to commit a mass shooting.

- As of August 2019, none of the order subjects went on to commit mass shootings, homicides, or die by suicide after the orders were issued.

- Extreme risk laws may be used to help prevent mass shootings.

Taken as a whole, these studies provide evidence that extreme risk laws are promising tools to help reduce gun violence — particularly firearm suicide.

Which States Have Extreme Risk Laws?

As of June 2021, nineteen states and the District of Columbia have extreme risk laws in effect.

Click on a state to learn more about state laws.

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- United States

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

California Law

California’s order is called a Gun Violence Restraining Order (Cal. Penal Code §§ 18100-18205). There are three types of orders available in California: emergency, temporary, and final. The emergency order is available only to law enforcement as petitioners and lasts up to 21 days after issuance. The temporary order is available to law enforcement and family or household members as petitioners and lasts up to 21 days after issuance. The final order is available to law enforcement and family or household members as petitioners and lasts one year. Effective September 1, 2020, employers, coworkers, and employees or teachers of a secondary or postsecondary school may petition for a temporary or final order. To learn more about California’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s California state page, SpeakForSafety.org, or California Courts.

Colorado Law

Colorado’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protection Order (Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 13-14.5-101 – 13-14.5-114). There are two types of orders available in Colorado: temporary and final. Law enforcement and family or household members may petition for both orders. The temporary order lasts up to 14 days after issuance and the final order lasts 364 days. To learn more about Colorado’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Colorado state page or Colorado Courts.

Connecticut Law

Connecticut’s order is called a Risk Protection Order or Risk Warrant (Conn. Gen. Stat. § 29-38c). Any family, household member, or medical professional may request a risk protection order investigation, but only law enforcement officers, a state’s attorney, or an assistant state’s attorney can apply for a risk warrant or protection order. Connecticut’s risk protection order has no predetermined end date; the respondent can petition for an order to be terminated after 180 days of it being granted. To learn more about Connecticut’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Connecticut state page or Connecticut Courts.

Delaware Law

Delaware’s order is called a Lethal Violence Protective Order (Del. Code Ann. tit. 10, §§ 7701-7709). There are two types of orders available in Delaware: emergency and final. Law enforcement and family members are eligible to petition for the emergency order, which lasts up to 10 days after issuance. Only family members are eligible to petition for the final order, which lasts up to one year. To learn more about Delaware’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Delaware state page.

District of Columbia Law

The District of Columbia’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protection Order (D.C. Code §§ 7-2510.10 – 7-2510.12). There are two orders available in the District of Columbia: ex parte and final. Law enforcement, family or household members, and mental health professionals are eligible to petition for both ex parte and final orders. The ex parte order lasts up to 10 days after issuance and the final order lasts for one year. To learn more about the District of Columbia’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s DC state page or DC Courts.

Florida Law

Florida’s order is called a Risk Protection Order (Fla. Stat. Ann. § 790.401). There are two orders available in Florida: temporary ex parte and final. Law enforcement is the only eligible petitioner for both orders. The temporary ex parte order lasts up to 14 days after issuance and the final order lasts up to one year. To learn more about Florida’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Florida state page or Florida Courts.

Hawaii Law

Hawaii’s order is called a Gun Violence Protective Order (Haw. Rev. Stat. §§ 134-61 – 134-72). There are two orders available in Hawaii: ex parte and final. Law enforcement, family or household members, medical professionals, educators, and work colleagues are eligible to petition for both orders. The ex parte order lasts up to 14 days and the final order lasts one year. To learn more about Hawaii’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Hawaii state page or Hawaii Courts.

Illinois Law

Illinois’s order is called a Firearms Restraining Order (430 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 67/1-67/80). There are two orders available in Illinois: ex parte and final. Law enforcement and family or household members are eligible to petition for both orders. The ex parte order lasts up to 14 days after issuance and the final order lasts six months. To learn more about Illinois’s law, visit: IllinoisProtectionOrder.org, SpeakForSafetyIl.org, or Implement ERPO’s Illinois state page.

Indiana Law

Indiana’s order is called a Seizure and Retention of a Firearm or Risk Warrant (Ind. Code Ann. §§ 35-47-14-1 – 35-47-14-10). There are two orders available in Indiana: warrant and warrantless. Only law enforcement is eligible to petition for the orders. The warrant lasts at least 180 days after issuance and the warrantless lasts at least 180 days after the court orders law enforcement to retain firearms. To learn more about Indiana’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Indiana state page or Indiana State Police Legal Office.

Maryland Law

Maryland’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protective Order (Md. Code Ann., Pub. Safety §§ 5-601 – 5-610). There are three orders available in Maryland: interim, temporary, and final. Law enforcement, family or household members, and healthcare professionals are eligible to petition for all three orders. The interim order lasts up to two business days, the temporary order lasts up to seven days after service, and the final order lasts up to one year. To learn more about Maryland’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Maryland state page or Maryland Courts.

Massachusetts Law

Massachusetts’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protection Order (Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 140, §§ 131R-131Y). There are two orders available in Massachusetts: emergency and final. Law enforcement and family or household members are eligible to petition for both orders. The emergency order lasts up to 10 days after issuance and the final order lasts up to one year. To learn more about Massachusetts’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Massachusetts state page or Massachusetts Courts.

Nevada Law

Nevada’s order is called an Order for Protection Against High-Risk Behavior (Nev. Rev. Stat. §§ 33.500 – 33.670). There are two orders available in Nevada: ex parte and final. Law enforcement and family or household members are eligible to petition for both orders. The ex parte order lasts up to seven calendar days after issuance or until the final hearing is held and the final order lasts up to one year. To learn more about Nevada’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Nevada state page.

New Jersey Law

New Jersey’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protective Order (NJ Stat. Ann. §§ 2C:58-20 – 2c:58-32). There are two orders available in New Jersey: temporary and final. Law enforcement and family or household members are eligible to petition for both orders. The temporary order lasts up to ten days after the petition is filed and the final order lasts one year. To learn more about New Jersey’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s New Jersey state page or New Jersey Courts.

New Mexico Law

New Mexico’s order is called an Extreme Risk Firearm Protection Order (S.B. 5, 54th Leg., 2d Sess. (N.M. 2020). There are two orders available in New Mexico: temporary and final. Only law enforcement officers are eligible to petition for both orders. The temporary order lasts up to ten days after issuance and the final order lasts up to one year.

New York Law

New York’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protection Order (N.Y. C.P.L.R. §§ 6340 – 6347). There are two orders available in New York: temporary and final. Law enforcement, district attorneys, family or household members, and school administrators or designees are eligible to petition for both orders. The temporary order lasts up to six days after service and the final order lasts up to one year. To learn more about New York’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s New York state page or New York Courts.

Oregon Law

Oregon’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protection Order (Or. Rev. Stat. §§ 166.525-166.543). There is one order available in Oregon: final. Law enforcement and family or household members are eligible to petition. The final order lasts one year. To learn more about Oregon’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Oregon state page or Oregon Courts.

Rhode Island Law

Rhode Island’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protection Order (R.I. Gen. Laws Ann. §§ 8-8.3-1 – 8-8.3-14). There are two orders available in Rhode Island: temporary and final. Only law enforcement may petition for both orders. The temporary order lasts up to fourteen days after issuance and the final order lasts one year. To learn more about Rhode Island’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Rhode Island state page or Rhode Island Courts.

Vermont Law

Vermont’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protection Order (Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, §§ 4051-4061). There are two orders available in Vermont: temporary ex parte and final. State’s attorneys and the office of the attorney general are only eligible to petition for both orders. The temporary ex parte order lasts fourteen days after issuance and the final order lasts up to six months. To learn more about Vermont’s law, visit: Implement ERPO’s Vermont state page or Vermont Judiciary.

Virginia Law

Virginia’s order is called a Substantial Risk Order. There are two orders available in Virginia: emergency and final. Law enforcement officers and Commonwealth Attorneys are eligible to petition for both orders. The emergency order lasts up to 14 days after issuance and the final order lasts up to 180 days.

Washington Law

Washington’s order is called an Extreme Risk Protection Order (Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §§ 7.94.010-7.94.900). There are two orders available in Washington: ex parte and final. Law enforcement and family or household members are eligible to petition for both orders. The ex parte order lasts up to fourteen days after issuance and the final order lasts one year. To learn more about Washington’s law, visit: ProtectionOrder.org or Implement ERPO’s Washington state page.

Learn More: Comparison of Extreme Risk Laws by State

Learn More: Comparison of Extreme Risk Laws by State

| STATE Name of order | PETITIONERS[*] Types of orders | ORDERS AVAILABLE Length of orders Burden of proof |

CALIFORNIA Gun Violence Cal. Penal Code §§ 18100-18205 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER EMPLOYER* COWORKER* SECONDARY OR POSTSECONDARY EMPLOYEE OR TEACHER* | EMERGENCY TEMPORARY FINAL |

COLORADO Extreme Risk Protection Order Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 13-14.5-101 – 13-14.5-114 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER | TEMPORARY FINAL |

CONNECTICUT Risk Protection Order Conn. Gen. Stat. § 29-38c | LAW ENFORCEMENT* [ASSISTANT] STATE’S ATTORNEY*

| RISK WARRANT RISK PROTECTION ORDER |

DELAWARE Lethal Violence Del. Code Ann. tit. 10, §§ 7701-7709 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY MEMBER | EMERGENCY FINAL |

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Extreme Risk D.C. Code §§ 7-2510.01 – 7-2510.12 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS | EX PARTE FINAL |

FLORIDA Risk Protection Order Fla. Stat. Ann. § 790.401 | LAW ENFORCEMENT | TEMPORARY EX PARTE FINAL |

HAWAII Gun Violence Protective Order | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL EDUCATOR WORK COLLEAGUE | EX PARTE FINAL |

ILLINOIS Firearms 430 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 67/1-67/80 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER | EX PARTE FINAL |

INDIANA Seizure and Retention of a Firearm (Risk-Warrant) Ind. Code Ann. §§ 35-47-14-1 – 35-47-14-10 | LAW ENFORCEMENT | WARRANT WARRANTLESS |

MARYLAND Extreme Risk Md. Code Ann., Pub. Safety §§ 5-601 – 5-610 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL | INTERIM TEMPORARY FINAL |

MASSACHUSETTS Extreme Risk Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 140, §§131R-131Y | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER | EMERGENCY FINAL |

NEVADA Order for Protection Against High-Risk Behavior Nev. Rev. Stat. §§ 33.500 – 33.670 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER | EX PARTE FINAL (EXTENDED) |

NEW JERSEY Extreme Risk NJ Stat. Ann. §§ 2C:58-20 – 2c:58-32 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER | TEMPORARY FINAL |

NEW MEXICO Extreme Risk Firearm S.B. 5, 54th Leg., 2d Sess. (N.M. 2020) | LAW ENFORCEMENT | TEMPORARY FINAL |

NEW YORK Extreme Risk N.Y. C.P.L.R. §§ 6340 – 6347 | LAW ENFORCEMENT DISTRICT ATTORNEY FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER SCHOOL ADMINISTRATOR OR DESIGNEE | TEMPORARY FINAL |

OREGON Extreme Risk Or. Rev. Stat. §§ 166.525-166.543 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER | FINAL* |

RHODE ISLAND Extreme Risk R.I. Gen. Laws Ann. §§ 8-8.3-1 – 8-8.3-14 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Temporary, Final | TEMPORARY FINAL |

VERMONT Extreme Risk Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, §§ 4051-4061 | STATE’S ATTORNEY OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL | TEMPORARY EX PARTE FINAL |

VIRGINIA Substantial Risk Order S.B. 240, 2020 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Va. 2020) | LAW ENFORCEMENT COMMONWEALTH ATTORNEYS | EMERGENCY FINAL |

WASHINGTON Extreme Risk Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §§ 7.94.010-7.94.900 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER | EX PARTE FINAL |

[*]We use the term “family or household member” to include petitioners such as parents or guardians, spouses, dating partners, and roommates. Please see state laws for the complete list of petitioners in each state.

Learn More: Comparison of Extreme Risk Laws by State

| STATE Name of order | PETITIONERS[*] Types of orders | ORDERS AVAILABLE Length of orders Burden of proof |

| CALIFORNIA Gun Violence Cal. Penal Code §§ 18100-18205 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Emergency, Temporary, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Temporary, FinalEMPLOYER* Temporary, FinalCOWORKER* Temporary, FinalSECONDARY OR POSTSECONDARY EMPLOYEE OR TEACHER* Temporary, Final*Effective September 1, 2020: employer, coworker who has substantial and regular interactions with the person and approval of their employer, or an employee or teacher of a secondary or postsecondary school, with the approval of a school administrator or a school administration staff member with a supervisorial role, that the person has attended in the last six months may petition for a temporary or final order. | EMERGENCY Up to 21 days after issuance Reasonable causeTEMPORARY Up to 21 days after issuance Substantial likelihoodFINAL One to five* years Clear and convincing*Effective September 1, 2020 |

| COLORADO Extreme Risk Protection Order Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 13-14.5-101 – 13-14.5-114 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Temporary, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Temporary, Final | TEMPORARY Up to 14 days after issuance Preponderance of the evidenceFINAL 364 days Clear and convincing |

| CONNECTICUT Seizure of Firearms Conn. Gen. Stat. § 29-38c | LAW ENFORCEMENT Warrant, Final[ASSISTANT] STATE’S ATTORNEY Warrant, Final | WARRANT Up to 14 days after execution Probable causeFINAL Up to 1 year Clear and convincing |

| DELAWARE Lethal Violence Del. Code Ann. tit. 10, §§ 7701-7709 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Emergency, FinalFAMILY MEMBER Final | EMERGENCY Up to 10 days after issuance Preponderance of the evidenceFINAL Up to 1 year Clear and convincing |

| DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Extreme Risk D.C. Code §§ 7-2510.01 – 7-2510.12 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Ex Parte, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Ex Parte, FinalMENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS Ex Parte, Final | EX PARTE Up to 10 days after issuance Probable causeFINAL One year Preponderance of the evidence |

| FLORIDA Risk Protection Order Fla. Stat. Ann. § 790.401 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Temporary Ex Parte, Final | TEMPORARY EX PARTE Up to 14 days after issuance Reasonable causeFINAL Up to 1 year Clear and convincing |

| HAWAII Gun Violence Protective Order | LAW ENFORCEMENT Ex Parte, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Ex Parte, FinalMEDICAL PROFESSIONAL Ex Parte, FinalEDUCATOR Ex Parte, FinalWORK COLLEAGUE Ex Parte, Final | EX PARTE Up to 14 days after petition for a one-year order submitted Probable causeFINAL 1 year Preponderance of the evidence |

| ILLINOIS Firearms 430 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 67/1-67/80 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Ex Parte, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Ex Parte, Final | EX PARTE Up to 14 days after issuance Probable causeFINAL 6 months Clear and convincing |

| INDIANA Seizure and Retention of a Firearm (Risk-Warrant) Ind. Code Ann. §§ 35-47-14-1 – 35-47-14-10 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Warrant, Warrantless | WARRANT At least 180 days after issuance Probable cause (initial warrant) Clear and convincing (at hearing)WARRANTLESS At least 180 days after the court orders law enforcement to retain firearm Probable cause (after firearm seizure) Clear and convincing (at hearing) |

| MARYLAND Extreme Risk Md. Code Ann., Pub. Safety §§ 5-601 – 5-610 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Interim, Temporary, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Interim, Temporary, FinalHEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL Interim, Temporary, Final | INTERIM Up to 2 business days Reasonable groundsTEMPORARY Up to 7 days after service Reasonable groundsFINAL Up to 1 year Clear and convincing |

| MASSACHUSETTS Extreme Risk Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 140, §§131R-131Y | LAW ENFORCEMENT Emergency, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Emergency, Final | EMERGENCY Up to 10 days after issuance Reasonable causeFINAL Up to 1 year Preponderance of the evidence |

| NEVADA Order for Protection Against High-Risk Behavior Nev. Rev. Stat. §§ 33.500 – 33.670 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Ex Parte, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Ex Parte, Final | EX PARTE Up to 7 days after issuance or until final hearing held Preponderance of the evidenceFINAL (EXTENDED) Up to 1 year Clear and convincing |

| NEW JERSEY Extreme Risk NJ Stat. Ann. §§ 2C:58-20 – 2c:58-32 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Temporary, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Temporary, Final | TEMPORARY Up to 10 days after petition is filed Good causeFINAL 1 year Preponderance of the evidence |

| NEW MEXICO Extreme Risk Firearm S.B. 5, 54th Leg., 2d Sess. (N.M. 2020) | LAW ENFORCEMENT Temporary, Final | TEMPORARY Up to 10 days after issuance Probable causeFINAL Up to 1 year Preponderance of the evidence |

| NEW YORK Extreme Risk N.Y. C.P.L.R. §§ 6340 – 6347 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Temporary, FinalDISTRICT ATTORNEY Temporary, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Temporary, FinalSCHOOL ADMINISTRATOR OR DESIGNEE Temporary, Final | TEMPORARY Up to 6 days after service Probable causeFINAL Up to 1 year Clear and convincing |

| OREGON Extreme Risk Or. Rev. Stat. §§ 166.525-166.543 | LAW ENFORCEMENT FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Final | FINAL* 1 year Clear and convincing*Court may issue a final order at an ex parte hearing. Respondent may request a hearing to terminate the order within 30 days of service. |

| RHODE ISLAND Extreme Risk R.I. Gen. Laws Ann. §§ 8-8.3-1 – 8-8.3-14 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Temporary, Final | TEMPORARY Up to 14 days after issuance Probable causeFINAL 1 year Clear and convincing |

| VERMONT Extreme Risk Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, §§ 4051-4061 | STATE’S ATTORNEY Temporary, FinalOFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL Temporary, Final | TEMPORARY EX PARTE 14 days after issuance Preponderance of the evidenceFINAL Up to 6 months Clear and convincing |

| VIRGINIA Substantial Risk Order H.B. 674, 2020 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Va. 2020) S.B. 240, 2020 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Va. 2020) | LAW ENFORCEMENT Emergency, FinalCOMMONWEALTH ATTORNEYS Emergency, Final | EMERGENCY Up to 14 days after issuance Probable causeFINAL Up to 180 days Clear and convincing |

| WASHINGTON Extreme Risk Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §§ 7.94.010-7.94.900 | LAW ENFORCEMENT Ex Parte, FinalFAMILY OR HOUSEHOLD MEMBER Ex Parte, Final | EX PARTE Up to 14 days after issuance Reasonable causeFINAL 1 year Preponderance of the evidence |

[*]We use the term “family or household member” to include petitioners such as parents or guardians, spouses, dating partners, and roommates. Please see state laws for the complete list of petitioners in each state.

IMPLEMENT ERPO

Implement ERPO is a joint project of the Bloomberg American Health Initiative and EFSGV that was designed to be a central resource for those implementing extreme risk laws across the country. Implement ERPO shares information about the different state ERPO laws, training resources, media coverage, research, and advice from law enforcement professionals who are leading ERPO implementation efforts.

CONSORTIUM ERPO RECOMMENDATIONS 2020

In October 2020, the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy (Consortium) released “Extreme Risk Protection Orders: New Recommendations for Policy and Implementation.” Drawing on lessons from across the country, the Consortium builds upon its 2013 report and outlines recommendations to improve and enhance the effectiveness of the state-based gun violence prevention policy known as the extreme risk protection order (ERPO). Recommendations include expanding eligible ERPO petitioners to include licensed health care providers, clarifying that ERPOs should apply to minors, creating standards around reporting requirements and collection of data, and providing states with funding for implementation, among others. For more information, please visit our Consortium resource page.

Recommendations

Enact and implement state extreme risk laws to prevent tragedy before it occurs and support robust implementation through local, state, and federal funding.

Far too often, warning signs of tragedy are visible but legal tools to address them are limited. Extreme risk laws are state-level policies that empower law enforcement and other eligible petitioners to intervene and prevent tragedy before it occurs through extreme risk protection orders. We recommend:

- Evidence-based risk factors: Extreme risk laws should be based on behavioral risk factors for violence, for example, history or threats of violence. Extreme risk laws should properly protect due process rights. A mental illness diagnosis should not be included as a determining factor for an extreme risk protection order.

- Petitioners: A key principle behind extreme risk protection orders is that they allow for law enforcement and the people closest to the respondent to intervene to help prevent tragedies before they occur. Eligible petitioners for extreme risk protection orders should include: 1) law enforcement officers; 2) family members, household members, and intimate partners; and 3) licensed healthcare providers.

- Cases involving minors at risk of violence: Extreme risk protection orders, including ex parte orders, should be considered in cases where the respondent is a minor, regardless of legal firearm ownership, if the minor has access to a firearm or would otherwise be eligible to purchase a firearm while the order is in effect.

- Duration of orders: Temporary (ex parte) orders should be in effect for 2-3 weeks until a hearing at which the respondent has the opportunity to be heard. Final orders should be in effect for 1 year. Final orders should be eligible for renewal based on a petition filed within the final 90 days of the order. If no renewal petition is sought and granted, the order should expire automatically at the end of 1 year.

- Early termination: Respondents should have the option to petition one time for early termination of the order once it goes into effect, with the burden of proof being on the respondent to demonstrate that they are no longer at elevated risk of violence.

- NICS: States should report all extreme risk protection orders to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), including their expiration dates and any renewals that are granted. The FBI’s NICS section should subsequently enter state-supplied extreme risk protection order data into the NICS systems and utilize these data as firearm prohibitors at the point of firearm purchases. Congress should appropriate funding for NICS to implement the use of extreme risk protection orders as firearm prohibitors at the point of firearm purchases.

- Data collection and sharing: Extreme risk protection order data should be made available to researchers, and aggregate data should be made available publicly. Data collection is key to understanding how extreme risk protection orders are being used and to ensure they are being used equitably.

- Implementation and evaluation: States and or local jurisdictions should establish a multidisciplinary working group(s) responsible for ensuring compliance and addressing challenges as they arise; developing and distributing relevant policies, materials, and training for a wide variety of stakeholders; educating the public; improving storage facilities and record keeping; and strategically evaluating extreme risk laws. States should dedicate adequate resources to support these activities.

- Funding for implementation: States and localities should allocate funding to ensure proper implementation and effective education of the public about these laws. Congress should provide funding to states and localities to support robust and equitable implementation of extreme risk laws.

Resources

Educational Materials

Fact sheets

- Summary of Research on Extreme Risk Laws

- Data Behind Extreme Risk Laws

- Data Behind Connecticut's Risk-Warrant Law

- Extreme Risk Laws Frequently Asked Questions

- Extreme Risk Laws One-Pager

- A Working Guide Towards More Racially Equitable Extreme Risk Laws

- Extreme Risk Laws vs. Domestic Violence Restraining Orders – How are they Different?

- Substantial Risk Orders (SROs) in Virginia

- Extreme Risk Laws and Due Process

- Limiting Access to Lethal Means: Applying the Social Ecological Model for Firearm Suicide Prevention

Reports

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders: New Recommendations for Policy and Implementation.

- Extreme Risk Laws: A Toolkit for Developing Life-Saving Policy in Your State

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders: An Opportunity to Save Lives in Washington State

- Guns, Public Health, and Mental Illness: An Evidence-Based Approach for State Policy

- Guns, Public Health, and Mental Illness: An Evidence-Based Approach for Federal Policy

Read More

- October 2019 op-ed in The Hill, Congress can prevent gun violence with protection laws and federal funding

- August 2019 blog, The story of ERPO

- March 2019 blog, It’s time to retire the term “Red Flag Laws”

- September 2017 blog, Setting the record straight on gun violence prevention

- May 2017 blog, California has the tools to prevent gun deaths. It is up to citizens to use them

- February 2017 op-ed in The Hill, Hypocrites at NRA aren’t fooling anyone

- June 2016 op-ed in Huffington Post, A gun law that could have prevented the Orlando massacre

Research

- Barry CL, Webster DW, Stone E, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS, & McGinty EE. (2018). Public support for gun violence prevention policies among gun owners and non–gun owners in 2017. American Journal of Public Health.

- Blocher J & Charles J. (2020). Firearms, extreme risk, and legal design. Virginia Law Review.

- Bonnie RJ & Swanson JW. (2018). Extreme risk protection orders – Effective tools for keeping guns out of dangerous hands. Developments in Mental Health Law.

- Frattaroli S, Hoops K, Irvin NA, McCourt A, Nestadt PS, Omaki E, Shields WC, & Wilcox HC. (2019). Assessment of physician self-reported knowledge and use of Maryland’s extreme risk protection order law. JAMA.

- Frattaroli S, McGinty EE, Barnhorst A, & Greenberg S. (2015). Gun violence restraining orders: Alternative or adjunct to mental health-based restrictions on firearms? Behavioral Sciences and the Law.

- Frizzell W & Chien J. (2019). Extreme risk protection orders to reduce firearm violence. Psychiatric Services.

- Gondi S, Pomerantz AG, & Sacks CA. (2019). Extreme risk protection orders: An opportunity to improve gun violence prevention training. Academic Medicine.

- Horwitz J, Grilley A, & Kennedy O. (2015). Beyond the academic journal: Unfreezing misconceptions about mental illness and gun violence through knowledge translation to decision makers. Behavioral Sciences and the Law.

- McGinty EE, Frattaroli S, Appelbaum PS, Bonnie RJ, Grilley A, Horwitz J, Swanson JW, & Webster DW. (2014). Using research evidence to reframe the policy debate around mental illness and guns: Process and recommendations. American Journal of Public Health.

- Parker GF. (2015). Circumstances and outcomes of a firearm seizure law: Marion County, Indiana, 2006–2013. Behavioral Sciences and the Law.

- Pallin R, Schleimer JP, Pear VA, & Wintemute GJ. (2019). Assessment of Extreme Risk Protection Order Use in California From 2016 to 2019. JAMA

- Roskam K & Chaplin V. (2017). The gun violence restraining order: An opportunity for common ground in the gun violence debate. Developments in Mental Health Law.

- Sklar T. (2019). Elderly gun ownership and the wave of state red flag laws: An unintended consequence that could help many. Elder Law Journal.

- Swanson JW. (2019). Understanding the research on extreme risk protection orders: varying results, same message. Psychiatric Services.

- Swanson JW, Easter MM, Alanis-Hirsch K, Belden CM, Norko MA, Robertson AG, Frisman LK, Lin H, Swartz MS, & Parker GF. (2019). Criminal justice and suicide outcomes with Indiana’s risk-based gun seizure law. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law.

- Swanson JW, Norko MA, Lin HJ, Alanis-Hirsch K, Frisman LK, Baranoski MV, Easter MM, Robertson AG, Swartz MS, & Bonnie RJ. (2017). Implementation and effectiveness of Connecticut’s risk-based gun removal law: Does it prevent suicides? Law and Contemporary Problems.

- Vernick JS, Alcorn T, & Horwitz J. (2017). Background checks for all gun buyers and gun violence restraining orders: State efforts to keep guns from high-risk persons. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics.

- Wintemute GJ, Pear VA, Schleimer JP, Pallin R, Sohl S, Kravitz-Wirtz N, et al. (2019). Extreme risk protection orders intended to prevent mass shootings: A case series. Annals of Internal Medicine.

Additional Resources

- 60 Minutes segment featuring Ed Fund Executive Director Josh Horwitz: A look at Red Flag laws and the battle over one in Colorado

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention: Extreme risk protection orders

- Cassidy J. (2018). A Glimmer of Hope in the Political Impasse on Gun Control. The New Yorker.

- Extreme Risk Protection Order: A Tool to Save Lives - Bloomberg American Health Initiative. The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence partnered with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg American Health Initiative to create a website which provides information and technical support for implementing Extreme Risk Laws.

- King County Regional Domestic Violence Firearms Enforcement Unit

- NAMI: Extreme risk protection orders

- Video recording and Witness Testimony from the Senate Judiciary Full Committee Hearing “Red Flag Laws: Examining Guidelines for State Action”

- San Diego City Attorney Office’s training materials for law enforcement agencies on Gun Violence Restraining Orders (GVROs)

- Speak for Safety - California, Speak for Safety - Illinois. The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence assisted in creating the Speak for Safety resources. These websites raise awareness of the Gun Violence Restraining order (GVRO) in California, and the Firearms Restraining Order (FRO) in Illinois.

- Nestadt P. (2020). Opinion: Extreme risk protection orders can prevent suicide. The Washington Post.

- Webinar Video: Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy: New Recommendations for Extreme Risk Protection Orders

- Webinar Video: Best Practices for Extreme Risk Protection Orders (ERPO) in the Wake of Indiana Shooting

Last updated June 2021