Nonfatal Gun Violence

Background

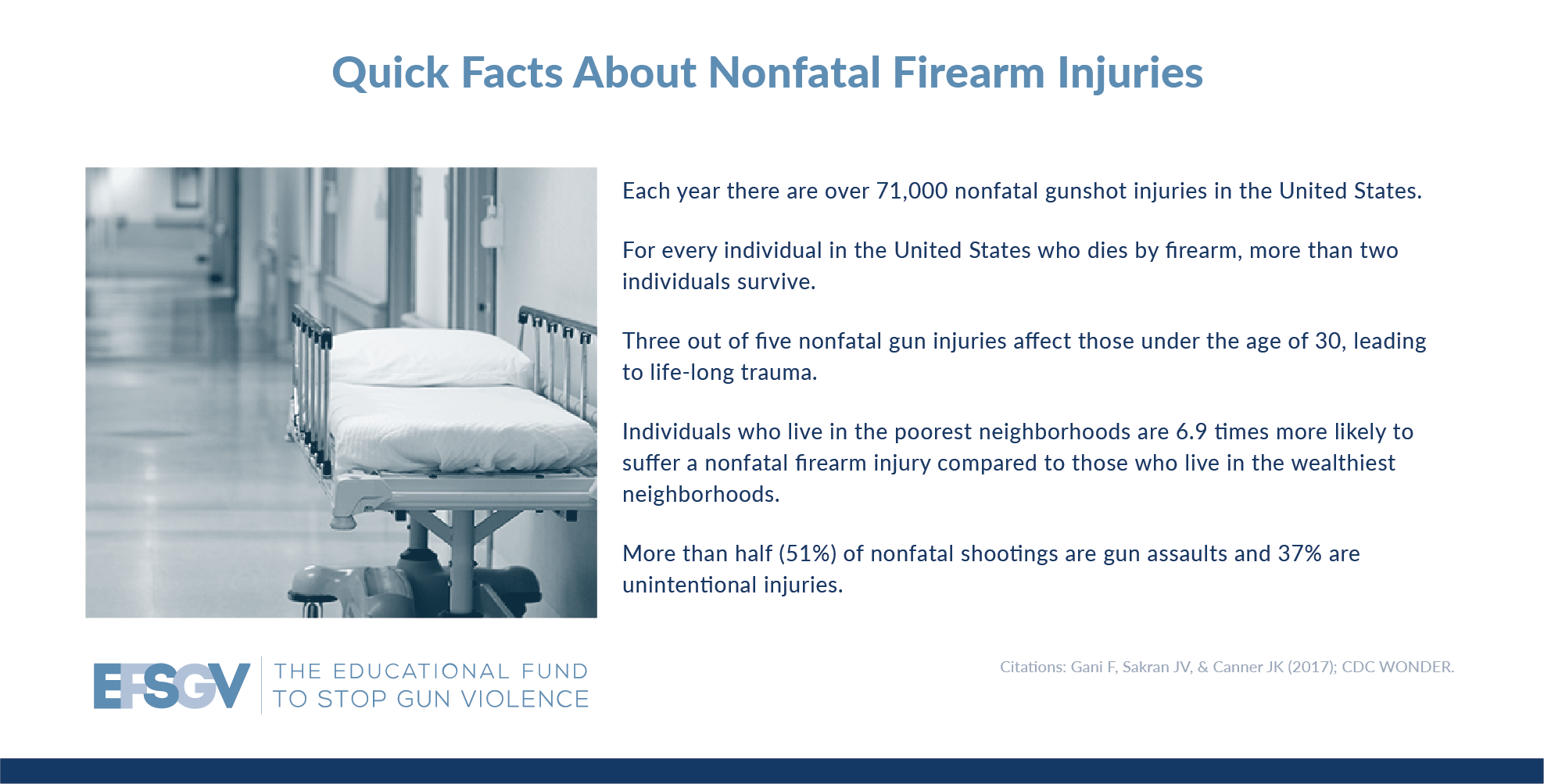

Millions of Americans living today have survived gun injuries and are coping with the associated physical pain and mental trauma. The accumulated costs of this trauma on our country is immeasurable. We must address this public health crisis of both fatal and nonfatal gun violence that plagues our nation. Future generations should not have to grow up with the physical and emotional scars that far too many Americans must live with today.

While increasing attention has shed light on the epidemic of gun deaths in the United States, far less is known about the millions of Americans who have survived gun violence. Unfortunately, publicly available and precise data on nonfatal gun injuries is limited and often not easily accessible. The data available highlights that each year an estimated 71,000 Americans are treated in emergency departments for nonfatal firearm injuries.6 Over half of these cases are a result of a firearm assault and an additional 37% are unintentional injuries. Young adults are disproportionately impacted by nonfatal gun violence, accounting for the majority of emergency department visits. Likewise, individuals living in poor neighborhoods face an unequal burden of nonfatal gun violence. They are nearly 7 times more likely to suffer from a gunshot wound than individuals living in wealthy neighborhoods.7

Impact of Nonfatal Gun Violence

There are many forms of nonfatal gun injury, all of which impact health and wellbeing. Survivors of gun violence include both those who experienced a direct physical injury and those who have been psychologically injured by the threat of gun violence. For example, abusers often use the mere presence of a gun to coerce, threaten, and terrorize their victims, inflicting enormous psychological damage.8 An estimated 4.5 million women living in the United States have been threatened with a gun by an intimate partner.9 Likewise, the trauma associated with witnessing gun violence is also a form of nonfatal gun violence, which can have lasting impacts on health, wellbeing, and development.10 The following data presented on this page focuses on the impact to those who are physically injured by a gun and who were admitted into an emergency department.

Physical Impacts

Each year there are over 71,000 visits to the emergency department for nonfatal gun violence.11 These injuries include unintentional shootings, assaults, and intentional self-injury – and the severity ranges significantly. Approximately 40% of individuals admitted to the emergency department experience relatively minor physical injuries and are treated and released from the emergency department.12 The other 60% of nonfatal gun injury patients admitted to the emergency department face more severe gunshot injuries and are hospitalized.13

Many of these survivors experience injuries that have lifelong impacts on mobility, cognitive function, and both psychological and physical wellbeing. One study found that over 13% of nonfatal gun injury patients will be readmitted into the hospital within the first six months of being discharged from medical care.14 Each year an estimated 1,470 individuals suffer traumatic brain injuries as a result of gunshot wounds. These individuals often spend weeks in intensive care, months in rehabilitation, and require ongoing medical care.15 Likewise, thousands of Americans suffer from gunshot wounds to the spinal cord. Gunshot wounds are the third most common form of spinal cord injury behind car crashes and falls.16 These spinal cord injuries often leave the survivor of gun violence with lifelong neurological deficits and paralysis, and they often require intensive and sustained medical care.17 Thirty percent of all survivors of spinal cord injuries are re-hospitalized during any given year following the injury.18 Other survivors who suffered gunshot injuries to the chest or abdomen are also likely to be readmitted to the hospital after their release.19 Severe nonfatal gun injuries have tremendous social and economic costs to society in the form of healthcare costs, lost productivity, and reduced wellbeing.

Psychological Impacts

Survivors also face the psychological hardships associated with the trauma of being shot. Many survivors must cope both with the long-term physical impacts of lost mobility or functionality and with the closely linked psychological trauma of having their lives forever altered. For many, these psychological impacts can affect health and wellbeing long after they have recovered from the physical injuries. Studies that have followed up on patients after they were discharged from the hospital for gunshot wounds found that, for many, the trauma of what they went through impacted their social and emotional wellbeing and their ability to carry out daily living activities. For example, one study conducted eight months after patients were discharged found that post traumatic stress among patients was common — 39% of patients reported severe intrusive thoughts and 42% reported severe avoidance behavior.20 Similarly, a study that followed up on patients five to eight years after they were shot found that nearly half of all patients exhibited symptoms for PTSD, and on average these patients had worse mental and physical health compared to the general population. Notably, among individuals who had been shot, unemployment rates increased by 14% and substance use increased by 13% five to eight years after they had been shot.21

Gun Injury Estimates

The most reliable national estimates on nonfatal gun violence are based on reporting from the National Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), a nationally representative set of emergency departments. This database records emergency department visits for gun injuries as well as information about the intent of injury, and basic demographics of the patient (age, sex, and socioeconomic status). While this database provides researchers with important data, it doesn’t fully capture the extent of nonfatal gun injuries. Individuals who suffer minor physical gunshot wounds and do not seek treatment at an emergency department are not captured in these estimates. Likewise, those who experience nonfatal gun violence in the form of being threatened, intimidated, or emotionally abused with a gun are also not captured in this database. Finally, this database records emergency department visits, not individual people. Thus, in some cases, the same individual could visit the emergency department multiple times for nonfatal gunshot wounds and be counted multiple times.

How many Americans are injured by a gun?

According to research conducted using the NEDS database, the majority of people who visit the emergency department for gunshot wounds survive their injuries. There are approximately 77,497 emergency department visits for gunshot wounds annually.22 An estimated 71,080 of these visits involve Americans who are treated for nonfatal firearm injuries (representing 91.7% of all emergency department visits for gunshot wounds annually), while 6,416 (8.3%) individuals died either in the emergency department or later on while being treated in the hospital.23

Nonfatal Gun Injuries by Intent

The intent (assault, suicide, unintentional, undetermined, legal intervention+) of nonfatal gun injuries are recorded by clinicians and hospital staff based on the information they receive about the patient. Thus, the intent of nonfatal gun violence is not always known and in some cases misclassified. The coding guidelines from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) state that when the injury intent is unknown, the coders should default to accidental (unintentional) intent.24 Therefore the number of unintentional injuries is likely less than the number recorded, and the number of assaults is likely higher than reported.

An analysis of NEDS data from 2006-2014 shows that the majority (50.2%) of all emergency department visits for nonfatal shootings were gun assaults, followed by unintentional injuries (accounting for 36.7% of all emergency department visits).25 Nonfatal firearm suicide attempts make up only 3.6% of overall nonfatal firearm injuries. This is because firearm suicide attempts are almost always fatal – research consistently notes that nine out of ten firearm suicide attempts are fatal.26 Therefore, while suicides make up over 60% of gun deaths they only account for 3.6% of nonfatal gun injuries.27

Nonfatal Firearm Injuries by Intent

Average Annual Nonfatal Firearm Injuries (2006-2014)

- Assault 50.2% (35,648)

- Unintentional 36.7% (26,103)

- Suicide 3.6% (2,552)

- Undetermined Intent 7.1% (5,078)

- Legal Intervention 2.4% (1,700)

Source: Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13.

Nonfatal Gun Injuries by Age Group

Nonfatal gun injuries disproportionately impact young adults. Each year there are more than 7,100 emergency room visits for nonfatal gunshot wounds among children under the age of 18 and 36,000 visits among youth ages 18-29. Although youth ages 18-29 make up less than 17% of the population, their injuries account for over half of all emergency department visits for nonfatal firearm injuries.28 Many of these children and young adults incur trauma and physical disability that will last their entire lives.

Nonfatal Firearm Injuries by Age Group

Nonfatal Firearm Injury Rates (2006-2014)

Rate per 100,000

Source: Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13; US Census data.

Nonfatal Gun Injuries by Sex

Males are more likely to be injured by firearm homicide, suicide, and unintentional injuries than females. Males are over 8.4 times more likely to be injured by firearms compared to females.29

Nonfatal Firearm Injuries by Sex

Average Annual Nonfatal Firearm Injuries (2006-2014)

Male

89%

(63,248)

Female

11%

(7,775)

Source: Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13; US Census data.

Nonfatal Gun Injuries by Region

There is wide regional variation in nonfatal gun violence. Individuals who live in the South are twice as likely to be injured by a firearm compared to those living in the Northeast.30 This regional variation may be linked to the strength of state gun violence prevention laws. For example, states in the Northeast region tend to have stronger gun laws than states in the South.31 One study, which examined nonfatal firearm injury rates in 18 different states, found that after adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic differences, states with strong gun laws32 were associated with lower nonfatal firearm assaults, self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries.33

Nonfatal Firearm Injuries by Region

Nonfatal Firearm Injury Rates (2006-2014)

Rate per 100,000

Region

Source: Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13; US Census data.

Nonfatal Gun Injuries by Median Household Income

Research consistently notes that concentrated poverty, income inequality, and disadvantage are risk factors for interpersonal firearm violence.36 An analysis of the NEDS data highlights that nonfatal firearm injuries disproportionately impact individuals who live in low income neighborhoods. The analysis used the patient’s ZIP code to determine median household income and divided patients into income quartiles using the ZIP codes. Half (50.9%) of patients who suffered nonfatal firearm injuries were from the neighborhoods in the bottom income quartile (25% of the population) where the median household income is less than $41,000. Only 7.4% of all nonfatal gun injuries occur among individuals who live in the wealthiest quartile of the income scale where the median household income is over $67,000. Individuals who live in the poorest neighborhoods are 6.9 times more likely to suffer a nonfatal firearm injury compared to those who live in the wealthiest neighborhoods.37,38

Nonfatal Firearm Injuries by Household Income

Average Annual Number of Nonfatal Firearm Injuries (2006-2014)

Nonfatal firearm injuries

Median household income, quartile

Source: Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13.

Comparing Nonfatal Firearm Injuries to firearm fatalities

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report accurate estimates of gun deaths through the National Violent Deaths Reporting System (NVDRS). NVDRS uses death certificates, police reports, and hospital records to report information about the victim, the cause of death, and the circumstances surrounding their death.39 While the CDC also reports nonfatal firearm injury data, this data is unreliable. This is because the CDC calculates nonfatal firearm injury data using only a small sample of hospitals. This small sample creates extremely wide estimates of nonfatal injuries and can easily lead to misleading interpretations of the data. Because of these concerns, we have chosen to use the NEDS nonfatal firearm injury data. Listed below is a comparison of nonfatal firearm injury estimates derived from NEDS compared with the CDC’s estimates of firearm fatalities over the same years (2006-2014).40 Comparing nonfatal firearm injuries to firearm deaths can provide insights into the lethality of certain types of gun violence.

Overall Estimates

On average 103,289 Americans were shot by a firearm annually from 2006 to 2014. Of these, 32,208 Americans died, and there were 71,080 emergency department visits for nonfatal firearm injuries. This suggests that seven out of every ten (68.8%) Americans who are shot survive. It is important to highlight that this is not consistent across different injury intents.

The two charts below highlight the breakdown of the average number of annual fatal and nonfatal firearm injuries by intent from 2006-2014. The first chart displays the nonfatal firearm injuries broken down by intent, in comparison to the fatal firearm injuries (deaths) broken down by intent. The second chart includes the same information but is displayed differently – showing the intent broken down by nonfatal and fatal. Both graphs highlight how certain types of gun violence are more likely to result in nonfatal injuries, while others are more likely to result in fatality.

For example, as highlighted below, there are far more fatal firearm suicide deaths than nonfatal firearm suicide attempts. Alternatively, there are more nonfatal firearm assault and unintentional injuries than there are fatal injuries.

Average Annual Number of Fatal and Nonfatal Firearm Injuries by Intent (2006-2014)

Number of fatal and nonfatal firearm injuries

Source: CDC WONDER; Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13.

Average Annual Number of Fatal and Nonfatal Firearm Injuries by Intent (2006-2014)

Number of fatal and nonfatal firearm injuries

Source: CDC WONDER; Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13.

Firearm Assault

Based on the NEDS nonfatal gun injury data and the CDC gun fatality data, three out of every four (75%) assaults are nonfatal. This aligns with estimates calculated by other researchers who estimated that 78% of victims of firearm assaults survive their injuries.6

Percentage of Firearm Assault Injuries that are Fatal (2006-2014)

Fatal firearm injuries

25%

(11,675)

Nonfatal firearm injuries

75%

(35,648)

Source: CDC WONDER; Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13.

Firearm Suicide

A thorough body of research highlights how firearm suicide attempts are almost always fatal. This is illustrated in the data below which shows that while an average of 19,311 Americans died by firearm suicide from 2006 to 2014, there were only 2,552 emergency department patients who survived a firearm suicide attempt. Nine out of every ten individuals who attempt firearm suicide die. Research of firearm suicides from a number of different databases, including NEDS, consistently shows that the firearm suicide fatality rate is near 90%.6 While 2014 is the latest year NEDS nonfatal firearm injury data is publicly available and thus was used below, unfortunately, in the years following 2014, firearm suicide fatalities have increased to record numbers. In 2018, 24,432 Americans died by firearm suicide.6

To learn more, visit our website PreventFirearmSuicide.com.

Percentage of Firearm Suicide Injuries that are Fatal (2006-2014)

Fatal firearm injuries

88%

(19,311)

Nonfatal firearm injuries

12%

(2,552)

Source: CDC WONDER; Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13.

Unintentional

Unintentional firearm injuries account for 37% of nonfatal firearm injuries but only 1.7% of all gun deaths. The lethality of unintentional firearm injuries is far less than any other type of gun violence. According to the NEDS and CDC data, two out of every one-hundred unintentional firearm injuries is fatal. However, as previously mentioned, some nonfatal injuries classified as unintentional may actually be the result of an assault. Regardless, the vast majority of unintentional firearms injuries are not fatal.

Percentage of Unintentional Shooting Injuries that are Fatal (2006-2014)

Fatal firearm injuries

2%

(568)

Nonfatal firearm injuries

98%

(26,103)

Source: CDC WONDER; Analysis of NEDS data by Gani et al. Appendix 13.

Undetermined

There are many more nonfatal firearm injuries that are classified as undetermined than there are firearm fatalities. Over 7% of nonfatal firearm injuries are classified undetermined while less than 1% of all firearm deaths are classified as undetermined. This may be a result of differences in coding and the fact that the process of investigating the intent of a firearm death includes an analysis of police reports, death records, and hospital records while the coding process for nonfatal injuries in the emergency department is more limited. It is critical to improve reporting and reduce the number of nonfatal and fatal firearm injuries classified with undetermined intent.

Legal Intervention

The data involving police shootings is incomplete as there is no comprehensive database or reporting system to record police-involved shootings, and police departments are not required to report this data. According to the NEDS nonfatal firearm injury data, each year there are 1,700 visits to the emergency department for nonfatal firearm injuries as a result of legal intervention. Analysis of fatal police shootings conducted by the Washington Post finds that each year approximately 1,000 Americans are shot and killed by police.44 It is critical to ensure that all police-involved shootings, both fatal and nonfatal, are recorded by the federal government in a centralized database and are reported to the public through an accessible and easy-to-use database.

Improving Nonfatal Firearm Injury Data

As highlighted above, the most reliable data regarding nonfatal firearm injuries is from the National Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) database. This database is made available through the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), and it draws from 30 million emergency department visits annually.

Through this database, researchers can access the estimated annual number of emergency room visits for firearm injuries for free. However, the publicly available data does not provide nonfatal firearm injury estimates because it includes those who were admitted into the emergency department alive but who later died in care. To access more detailed information that includes whether patients died in the emergency department, researchers must purchase the NEDS data and have the statistical knowledge and software to properly analyze it. Yet, even this data does not allow for the types of in-depth investigations researchers and advocates can easily conduct with the fatal injury data available through CDC. For example, NEDS does not allow for in-depth analysis of subgroups based on race/ethnicity or specific states or counties.45

The CDC Plays a Vital Role in Providing Public Health Data to Researchers

Researchers need robust and reliable data to study and develop solutions to address the epidemic of gun violence in the United States. The CDC is the federal agency responsible for protecting Americans by ensuring that data is properly collected to develop solutions to our nation’s public health crises, including gun violence. The CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) plays an instrumental role for gun violence prevention advocates and researchers. The NVDRS uses death certificates, police reports, and hospital records to report information about the victim, the cause of death, and the circumstances surrounding their death.46 The CDC makes this data publicly available and easily accessible through their Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS).

While firearm fatality data is vital to researching gun violence in the United States, it does not provide the whole picture, especially for interpersonal gun violence. Without reliable data on nonfatal firearm injuries, researchers are limited in their ability to comprehensively investigate firearm violence and design effective interventions.

The CDC Reports Unreliable Nonfatal Gun Injury Estimates

The CDC calculates its estimates of nonfatal firearm injuries using a database operated by the Consumer Product Safety Commission called the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS). The CDC reports these estimates through WISQARS and this data is widely cited in academic articles and by the American public. However, the CDC’s nonfatal firearm estimates were calculated from a total of 60 hospitals in 2017 — which represent less than 2% of all hospitals across the country.47 This small sample leads to extremely broad estimates of nonfatal injuries and can easily lead to misleading interpretations of the data – especially when comparing trends over time or when examining the number of nonfatal firearm injuries within a small jurisdiction or sub-population.

A joint investigation by researchers at The Trace and FiveThirtyEight found that the CDC estimates were causing confusion among researchers and the public. The investigation highlighted that what appeared to be a 37% increase in nonfatal firearms injuries from 2015 to 2016 was merely a change in the sample of hospitals surveyed — not a statistically significant increase.48 The investigation also found that the imprecision of the CDC’s nonfatal injury estimates has increased by nearly four-fold since 2002. The CDC estimated that there is a 95% chance that somewhere between 31,000 and 236,000 individuals were injured by guns in 2017.49 After reporting by The Trace, the CDC has since removed these estimates from their online nonfatal injury database.50

By comparison, the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) database is drawn from over 30 million emergency room visits annually. This sample includes over 950 hospitals, accounting for approximately 20% of the hospital-based emergency departments in the United States.51 The NEDS sample is nearly 16 times larger than the sample of hospitals the CDC uses. This leads to much more precise estimates of the number of nonfatal firearm injuries. In other words, researchers and the public can reliably use the NEDS estimates to track and study nonfatal gun injuries, yet this data is not publicly available and is difficult to analyze.

Members of Congress Expressed Concern About the CDC’s Unreliable Estimates

On March 29, 2019, Senator Robert Menendez (D-NJ) and ten of his colleagues sent a letter to the Secretary of Health and Human Services criticizing the imprecise nonfatal firearm injury estimates and asking the CDC why they do not draw their data from a larger sample of hospitals like the NEDS database.52 An exchange ensued where the CDC defended their methodology and explained that they are looking into ways to produce more reliable estimates, while the senators pushed back and called for the CDC to take concrete steps to solve the problem.53 As a result of the public and political attention to this issue, the CDC has removed their most unreliable estimates of nonfatal firearm injuries from WISQARS and has investigated ways to improve their nonfatal firearm injury data.54

For a more in-depth description of how policymakers can improve nonfatal firearm injury see our fact sheet: Recommendations to Improve Nonfatal Gun Injury Data

Recommendations

Enact and implement policies, programs, and practices that reduce easy access to firearms by people at risk of violence and invest in interventions that address the root causes of gun violence; adequately fund services and support to gun violence survivors; and improve nonfatal firearm injury data collection and reporting procedures.

A fraction of an inch in a bullet’s trajectory can be the difference between a fatal and nonfatal injury. Preventing nonfatal gun violence relies on interventions that reduce easy access to firearms and investing in interventions that address the root causes of gun violence. See homicide, community violence, and unintentional shootings for more information.

Federal, state, and local policymakers should adequately fund services and support to gun violence survivors to ensure these individuals can live healthy and productive lives.

- Victims of Crimes Act (VOCA) funding: VOCA funds are designed to compensate victims of violence and to fund organizations that provide assistance to victims. To date, these funds have been underutilized to support victims of community gun violence. VOCA funds can be used to support a wide range of vital services such as hospital-based violence intervention programs, community-based violence prevention programs, and mental health services for those exposed to trauma. States should use their federal VOCA funds to provide services and compensation specifically to victims of community gun violence. They can do this by easing eligibility requirements and providing education and technical assistance to notify individuals and organizations that qualify for VOCA funds and help provide support to apply for the funds.

- Hospital-based Violence Intervention Programs: Gunshot victims who are admitted to hospitals should receive support through hospital-based violence intervention programs. These evidence-based programs provide survivors of gun violence with wraparound services such as educational support, job training, and culturally responsive mental health services to interrupt retaliatory cycles of violence and reduce the potential for re-injury.

- Trauma Informed Care: Trauma informed care recognizes and responds to the impact of trauma, emphasizing physical, psychological, and emotional safety, while promoting empowerment and healing. Trauma informed care helps individuals and communities cope with the trauma of community gun violence. Federal, state, and local policymakers should pass legislation to promote and adequately fund trauma informed practices across public agencies including in education, law enforcement, and social service providers.

In addition to policy, we recommend improving nonfatal firearm injury data collection and reporting procedures:

- Improve nonfatal firearm injury data: Strong data is the foundation of the public health approach. Robust and accurate nonfatal injury data is greatly needed to better understand nonfatal firearm injury and develop effective interventions for community violence. The number of hospitals included in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) database should be expanded, the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) data should be incorporated into the CDC’s Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) database to adjust the current online estimate, and a nonfatal shooting category should be added to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting program.

Resources

Educational Materials

Fact Sheet

Research

- Avraham JB, Frangos SG, & DiMaggio CJ. (2018). The epidemiology of firearm injuries managed in US emergency departments. Injury Epidemiology.

- Conner A, Azrael D, & Miller M. (2019). Suicide case-fatality rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: A nationwide population-based study. Annals of Internal Medicine.

- Cook PJ, Rivera-Aguirre AE, Cerdá M, & Wintemute G. (2017). Constant lethality of gunshot injuries from firearm assault: United States, 2003–2012. American Journal of Public Health.

- Gani F, Sakran JV, & Canner JK. (2017). Emergency department visits for firearm-related injuries in the United States, 2006–14. Health Affairs

- Greenspan AI, & Kellermann AL. (2002). Physical and psychological outcomes 8 months after serious gunshot injury. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery.

- Kalesan B, Zuo Y, Xuan Z, Siegel MB, Fagan J, Branas C, & Galea S. (2018). A multi-decade joinpoint analysis of firearm injury severity. Trauma surgery & acute care open. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care.

- Simonetti JA, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Mills B, Young B, & Rivara FP. (2015). State firearm legislation and nonfatal firearm injuries. American Journal of Public Health.

- Vella MA, Warshauer A, Tortorello G, Fernandez-Moure J, Giacolone J, Chen B, Cabulong A, Chreiman K, Sims C, Schwab CW, & Reilly PM. (2020). Long-term functional, psychological, emotional, and social outcomes in survivors of firearm injuries. JAMA surgery.

Additional Resources

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUPnet). This government database provides information on emergency departments and inpatient visits for firearm injuries.

- The state of firearms data in 2019: First report of the expert panel on firearms data infrastructure. This report by NORC at the University of Chicago provides an overview of the firearm databases available and discusses the strengths and weaknesses of each.

- Hospital Visits in the U.S. for Firearm Related Injuries, 2009. This statistical brief published by HCUP examines both inpatient and emergency department visits for nonfatal firearm injuries through 2009.

- The Trace, in partnership with FiveThirtyEight published a series of articles highlighting the accuracy of the CDC’s nonfatal injury data including:

Last updated July 2020